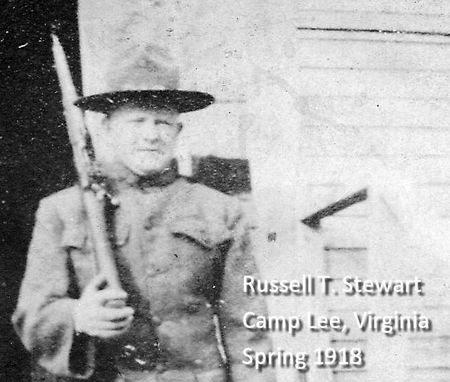

A Pittsburgh newspaper article published three months after the end of World War I highlights the battle at Imécourt, France.1 It was of particular interest to Pittsburgh readers because most of the men who fought there were from Pittsburgh. It was the final battle for the 319th Infantry Regiment, part of the 80th Division. Several men were killed in action there, including my granduncle, Russell T. Stewart.2

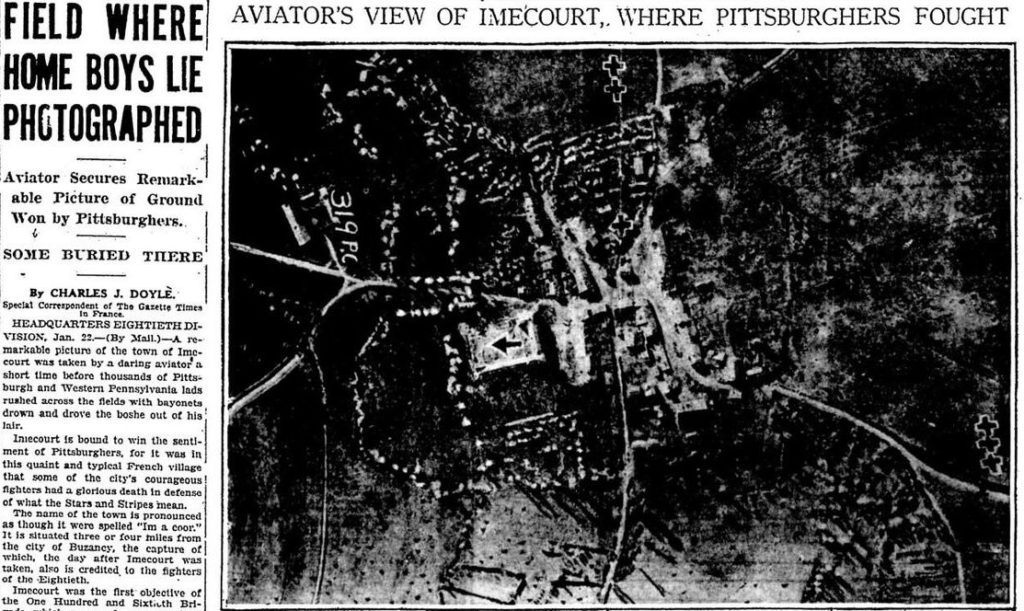

The article includes an aerial reconnaissance photograph, but it is barely discernible in this poor quality reproduction. Luckily the original army photo is still available.3 It is reproduced below in its correct orientation, with north upward. The markings mentioned in the article are included here, except the 1, 2, and 3 crosses are replaced instead by circled numbers.

Sent from the 80th Division headquarters, the article provides clues about the battle at Imécourt. Correspondent Charles J. Doyle was probably still in France and the 80th Division headquarters was still very much active there.

The photograph was “taken by a daring aviator a short time before thousands of Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania lads rushed across the fields.” The actual photo was indeed taken October 23, 1918 just days before the November 1 offensive.

The article goes on, “after passing the upper edge of town the enemy opened up a terrifying machine gun fire, which necessitated quick action on the part of Capt. Hooper, who was in charge of the Third Battalion.4 Capt. Hooper ordered the men to drop back into a friendly orchard and as it was getting dark, he commanded his fighters to find places of shelter for the night.”

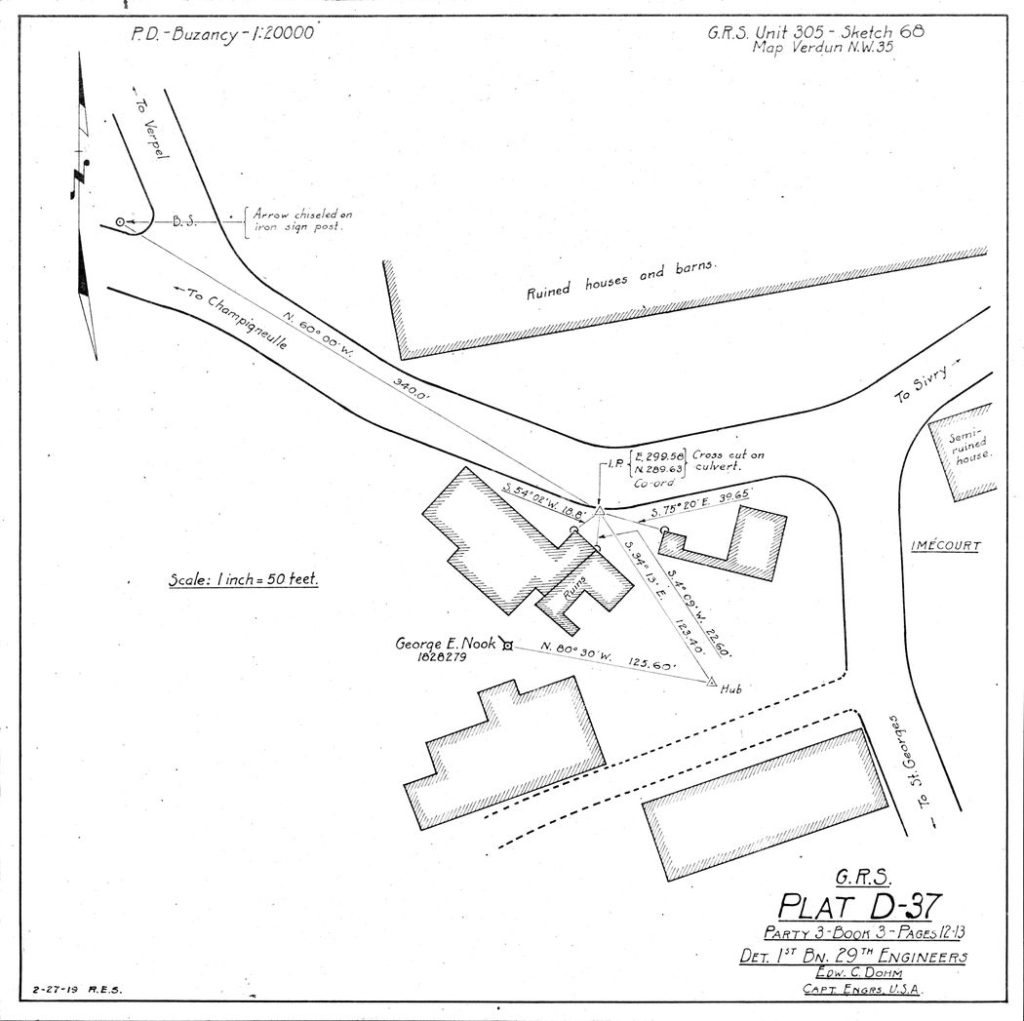

There does appear to be an orchard just to the left of the barn (1). The author spoke with several people including George E. Nook, who was in the barn hit by artillery. Mr. Nook was a mechanic in Company M and was killed November 1 near the barn mentioned. Since the author arrived at Imécourt November 2, it is doubtful he actually spoke with Mr. Nook.

The area denoted by (3) was “another scene of hard fighting. It was while leading his fighters on this main road to Buzancy that brave little Stephen Hoskins of Warren, Pa., fell.” Lt. Stephen Paul Hoskins5 was in Company G. He was killed November 2 and initially buried near the Chateau d’Imécourt. If he were indeed killed in this area, perhaps those buried next to him were in the same area.

Russell Stewart was in Company M. He was also killed November 2 and buried near Lt. Hoskins at the Chateau d’Imécourt. It is already known that Companies L and M were sent to the northern edge of the town.6

This may be the precise area where Russell was killed. However other evidence indicates a westward attack starting from this area took place early in the morning of November 2. So Russell probably died in the area to the left of (3).7

A Precarious Line

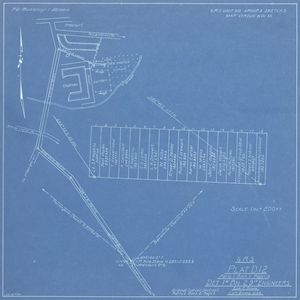

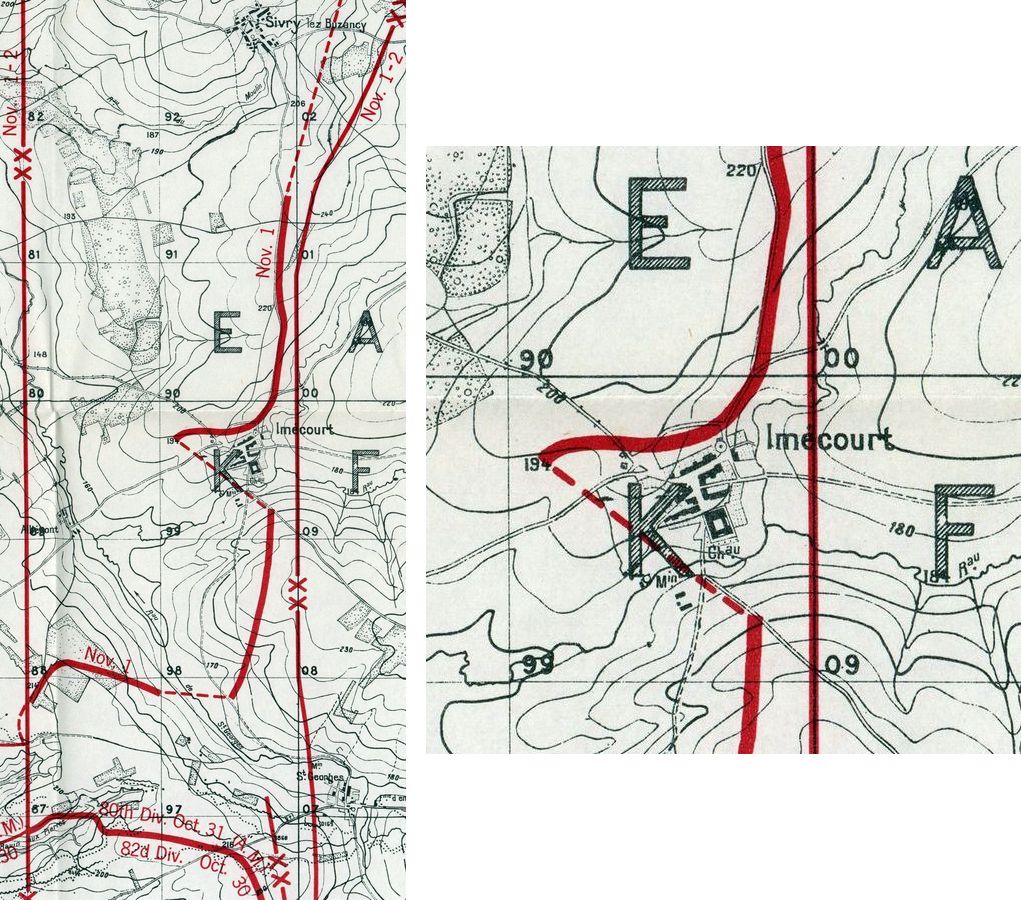

The tenuous front held the night of November 1, 1918 is shown in this army map.8 On the left of the zone, the 320th Infantry was held up by intense machine gun fire all day. They didn’t make it very far from the initial jump off point. To their right, the 319th did make it to Imécourt, but the dashed lines indicate areas where no troops were actually stationed. An enemy counterattack there would have been disastrous.

The detail of Imécourt at right shows the Chateau d’Imécourt as a square structure on the south edge of town. The front line to the west corresponds to area (2) in the aerial photo, while the line to the north depicts area (3).

Notice St. Georges at the bottom right on the map above. Howard C. Spencer with the 305th Engineers took this photograph as he marched from St. Georges to Imécourt later in the morning of November 1, 1918.9 His path would intersect with Russell Stewart’s that afternoon at Imécourt.

A photograph taken after the war shows the approach to Imécourt from the south, and the Sivry-Buzancy road off to the north, back, right.10

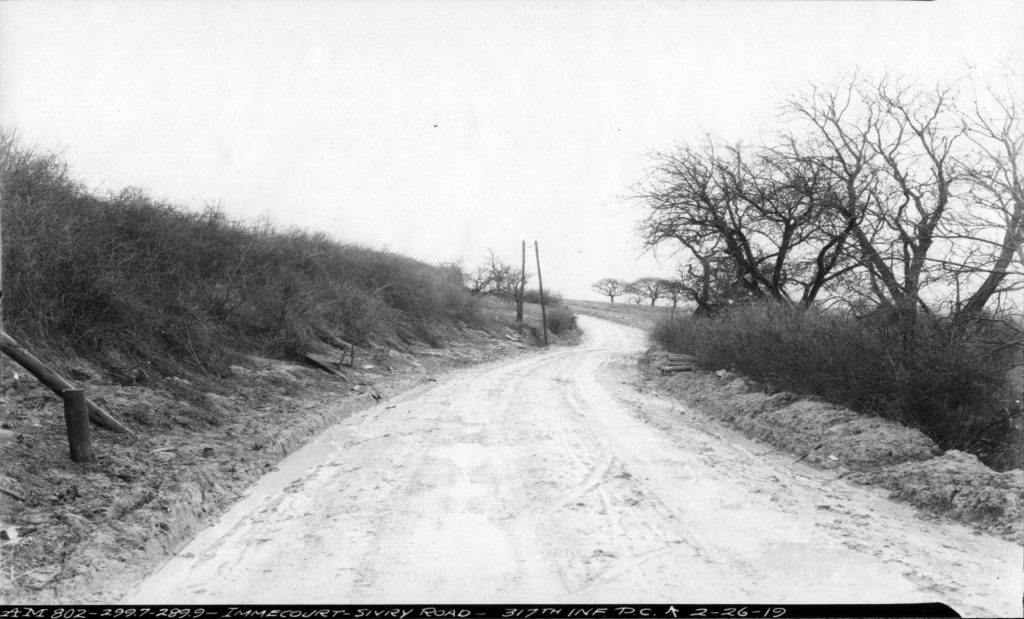

Another photograph shows the Sivry-Buzancy road north of Imécourt, likely near the area where Russell Stewart was stationed. It is marked as the 317th Infantry’s command post. They continued the battle here the next day, November 3, 1918.11

A Remarkable Photograph

Russell Stewart’s battalion remained in the area north of Imécourt, and defended it from several German counter-attacks all afternoon and into the night on November 1, 1918. Major Charles Rossire, Jr.12 refers to two companies of the support battalion that defended the Sivry-Buzancy road. We know from another source these were companies L and M.13

12:10 P. M. Enemy attempted to filter across Imecourt – Sivry Road at E9804 with Machine guns and drove back a detachment of engineers who were repairing the road. The Bn. Commander, leading Bn., happened to be at this point at the time and immediately sent for a platoon of the left support company. Seeing the vitality of the position, 2 companies of the support Bn. were also placed along the road at this point. This position lay off the flank of the reserves of the Division to our right. All that afternoon, repeated attempts were made by the enemy to force an opening at this position. Here again rifle grenades were used with great effect.

Actual battle photographs from this era are rare. The photo above may indeed be a remarkable intersection of family history with world history. It was taken by James C. Spencer, who served in the 305th Engineers, part of the 80th Division.14 A detachment of engineers from the 305th was assigned to repair the road between Imécourt and Sivry the afternoon of November 1. They were driven off by enemy gun fire.15 Russell’s battalion, and specifically Russell’s company, was sent to this very area to defend the road and probably also the army engineers trying to repair it. It was therefore taken in the area where Russell Stewart was, while he was there. Notice the helmets of soldiers in the photograph.

Destruction of the Chateau

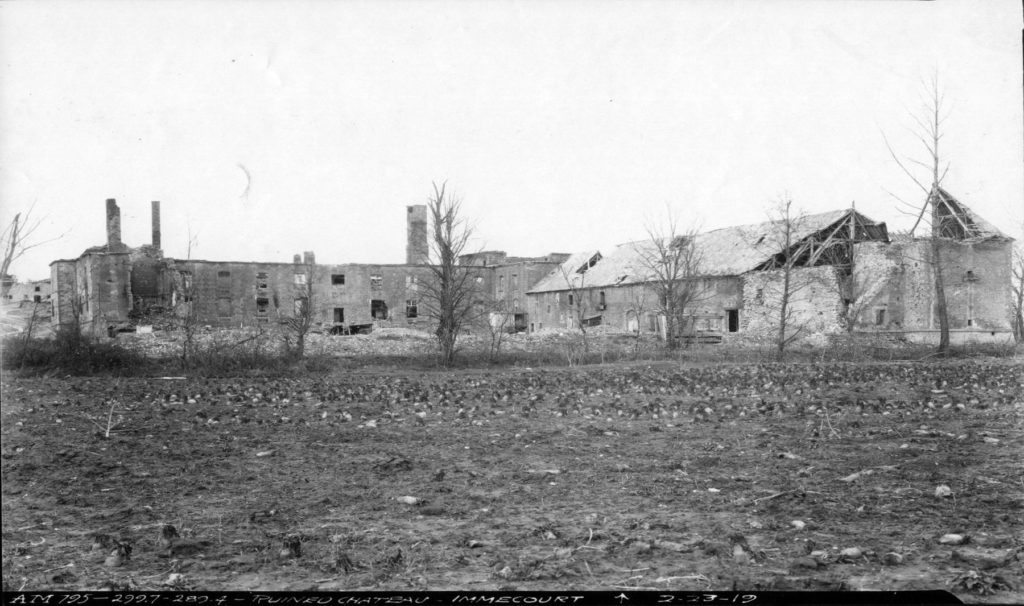

The newspaper article also mentions the Chateau d’Imécourt was blown up by an enemy time-delay fuse. That report was unconfirmed and the author suggests it was a rumor. Other unconfirmed reports indicate it was instead burned by an accidental fire while occupied by US troops.

A photograph taken February 23, 1919 shortly after the newspaper article was published, shows the Chateau was indeed destroyed.16 Although the roof is missing in most places, many of the walls are still standing. This damage looks more consistent with a fire than an explosion. However an incendiary device could have caused the fire.

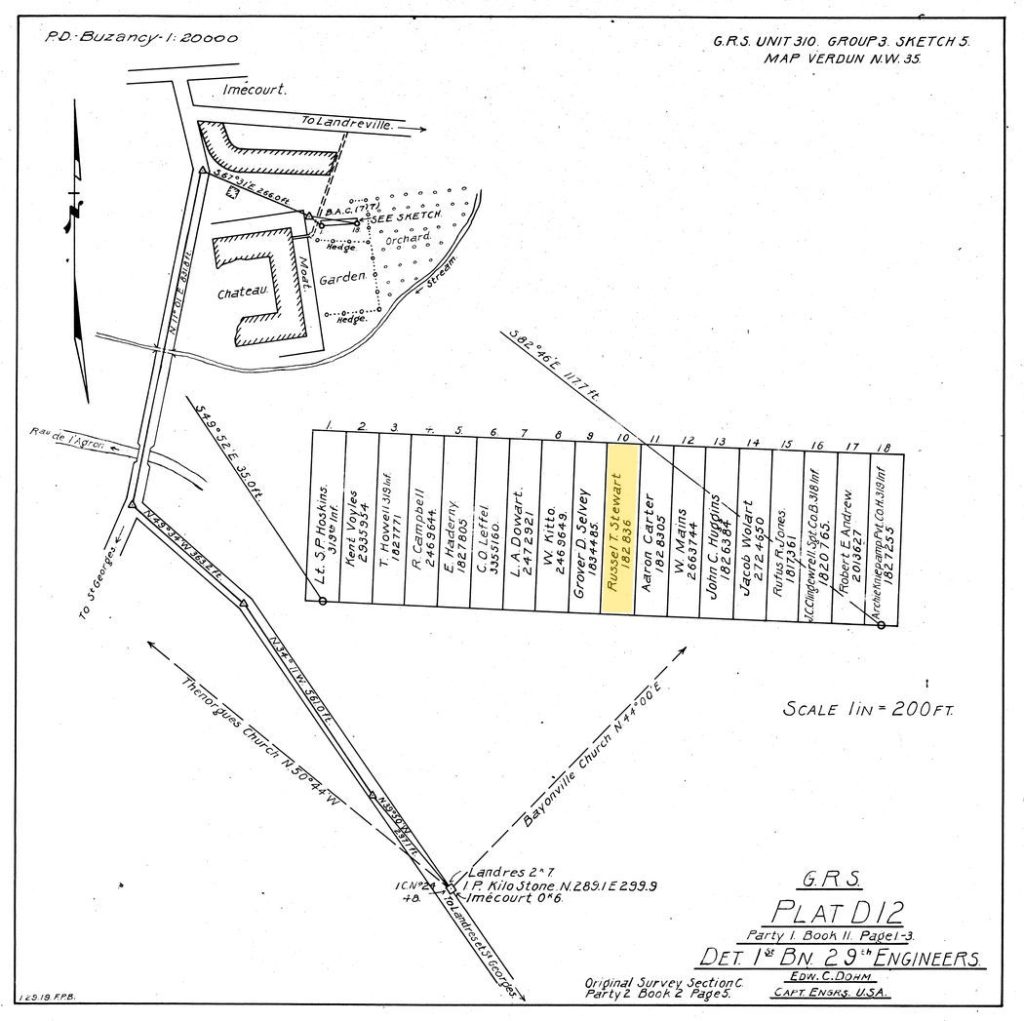

This survey17 shows the Chateau d’Imécourt and Army Cemetery 717, where Russell Stewart and Lt. Hoskins were initially buried. It was made before April 15, 1919, when Russell had been disinterred and reburied near Romagne. It shows the walls of the Chateau either before or after it was completely destroyed. Note the western side of the structure, which is missing, had already been destroyed by November 1, 1918.

These soldiers were buried in Army Cemetery 717 at the Chateau d’Imécourt:

| Plot | Name | Serial | KIA | Unit |

| 1 | Lt. Stephen P. Hoskins |

| Nov 2 | Company G |

| 2 | Pvt. Kent Voyles | 2935954 | Nov 2 | Company L |

| 3 | Pfc. Thomas Howell | 1827771 | Nov 2 | Company K |

| 4 | Pvt. Ralph Campbell | 2469644 | Nov 2 | Company K |

| 5 | Pvt. Ignacy Haderny | 1827805 | Nov 2 | Company K |

| 6 | Clarence O. Leffel | 3355160 |

| Cook |

| 7 | Cpl. Lee A. Dowart | 2472921 | Nov 2 | Company K |

| 8 | Pvt. William Kitto | 2469649 | Nov 2 | Company E |

| 9 | Pvt. Grover D. Selvey | 1834485 | Nov 2 | Company M |

| 10 | Pfc. Russell T. Stewart | 1828386 | Nov 2 | Company M |

| 11 | Pvt. Aaron Carter | 1828305 | Nov 2 | Company M |

| 12 | Pvt. William Mains | 2663744 | Nov 2 | Company E |

| 13 | Sgt. John C. Huggins | 1826384 | Nov 2 | Company E |

| 14 | Pvt. Jacob Wolart | 2724650 | Nov 2 | Company E, 302nd, 76th Division |

| 15 | Cpl. Rufus R. Jones | 1817361 |

| Company C, 317th |

| 16 | Sgt. John P. Clingemprell | 1820765 |

| Company B, 318th |

| 17 | Robert E. Andrew | 2013627 |

| Company C, 313th Machine Gun Battalion |

| 18 | Pfc. Archie Kniepkamp | 1827255 | Nov 1 | Company H |

Another survey shows the barn (1) mentioned in the article and the grave of George Nook, who was also mentioned. He was probably buried near where he fell.

Another aerial view taken along with the published photo shows the northern edge of Imécourt, where Russell Stewart and Stephen Hoskins were stationed.18 As mentioned in the article, numerous large shell craters dot the landscape.

Transcription

The Gazette Times article provides many clues about what actually happened at Imécourt. That it was published at all shows the importance of the battle at Imécourt to the citizens of Pittsburgh.

Field Where Home Boys Lie Photographed

Aviator Secures Remarkable Picture of Ground Won by Pittsburghers.

Some Buried There.By Charles J. Doyle, Special Correspondent of the Gazette Times in France.

Headquarters Eightieth Division, Jan. 22.–(By Mail.)–A remarkable picture of the town of Imecourt was taken by a daring aviator a short time before thousands of Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania lads rushed across the fields with bayonets [drawn] and drove the boshe out of his lair.

Imecourt is bound to win the sentiment of Pittsburghers, for it was in this quaint and typical French village that some of the city’s courageous fighters had a glorious death in defense of what the Stars and Stripes mean.

The name of the town is pronounced as though it were spelled “Im a coor.” It is situated three or four miles from the city of Buzancy, the capture of which, the day after Imecourt was taken, also is credited to the fighters of the Eightieth.

Imecourt was the first objective of the One Hundred and Sixtieth Brigade which was under command of Gen. Lloyd M. Brett. Crouching for hours—yes for a few hours more than a day and a night—between the fires of their own and enemy barrage, the doughboys were on their toes ready to spring at the zero hour, which was set for 6 o’clock on the morning of November 1, or just a short time before dawn.

Drive Goes Right On.

The Three Hundred and Nineteenth and Three Hundred and Twentieth fighters lay on the side of a hill near Sommerance, about five kilometers south of Imecourt, during the barrage. The Three Hundred and Twentieth was held up during most of the day by some terrible machine gun fire, but the Three Hundred and Nineteenth scrappers, having open fields in front of them for the most part, dashed on toward their first objective.

After chasing the Huns out of the little town, the boys from the great industrial center continued their drive in the general direction of Buzancy. But after passing the upper edge of town the enemy opened up a terrifying machine gun fire, which necessitated quick action on the part of Capt. Hooper, who was in charge of the Third Battalion. Capt. Hooper ordered the men to drop back into a friendly orchard and as it was getting dark, he commanded his fighters to find places of shelter for the night.

The building marked with the single cross [1] on the left hand side of the main road in the reproduction of the picture made by the aviator, printed herewith, looked inviting to a squad of snipers and runners who happened to be near that spot when the command was given. Chaplain Lee was also close to this building and he decided to pitch a bunk within the sheltering walls for the night.

Building Shelters Local Men.

That same old structure was destined to feel the fury of a Hun shell and crumble under its force before the night was over, but it looked like a port in a storm for the tired doughboys, the most of whom were soon asleep and remained at rest until the shell came thundering through the walls.

I afterward talked to many of the snipers and runners who were stretched out on the floor that memorable night. The names of some of these fighters with their home addresses follow:

Samuel Winski, Etna.

John Benedict, Duquesne.

Snuffy Snyder, Fair Haven.

Frank Penzi, Drabosburg.

Taylor Elown[?], St. Mary’s.

William Goodlin, Wall, Allegheny county.

Steve Doyle, Sharon.

Charles Toogood, Ambridge.

Emil Hopkins, Leetadale.

Fred Fisher, Castle Shannon.

George Nook, Coraopolis.The retreating Jerries shelled Imecourt that night. One of the destructive shells shrieked its way to the big barn, where it exploded, but, strange to say, the doughboys were left unharmed in the crumbling ruins.

Where Pittsburghers Died.

The two crosses [2] noted on the picture show the location of the German counter-attack which was met by the Pittsburghers, at least six of them making the great sacrifice in this vicinity. They were all members of the Third Battalion and were carefully buried near the scene.

Out the road that runs to the right [north] the reader will observe three crosses [3] which mark another scene of hard fighting. It was while leading his fighters on this main road to Buzancy that brave little Stephen Hoskins of Warren, Pa., fell. Hoskins had won his commission on this side and was the idol of his men. After being struck the alert stretcher bearers carried him back to the first aid station near the top of town, where he died among his good friends.

Members of the Eightieth Division, particularly the boys of the Three Hundred and Nineteenth and the Three Hundred and Twentieth, were astounded when the news was brought to them recently of the blowing up of the magnificent chateau in Imecourt, the best structure in the town by far. The great edifice, marked by an arrow in the picture, stood on an imposing plot on the right side of the main road. But if the authoritative reports are true it is now a mass of ruins, it having been destroyed by a German time fuse, according to the information furnished the Eightieth camp.

The Eightieth Division had its headquarters in the big building on the third day of the attack. It is reported that the building was blown up about a week after this date. The writer has not received any official verification of the report, but it is a matter of general comment in Eightieth circles.

Many Shell Craters.

The day after the Three Hundred and Nineteenth doughboys occupied the town, Col. Love and his staff, accompanied by the Gazette Times correspondent, moved up from Somerance to Imecourt and established a new P. C. in the cellar of a building near the entrance of the village. The building is the first noted in the picture.

The numberless marks in the ground which resemble ant hills show, in a mild way, the effect of the Allied barrage which preceded the drive of the doughboys. While the high altitude photograph makes them appear as almost on the surface of the ground, they are in fact big shell holes, many of them 10 feet in diameter and very deep.

The One Hundred and Sixtieth Brigade boys say the fighting as a whole on the last great offensive could hardly be compared with the severe fighting in the Argonne Forests, but they left quite a few of their pals in and about Imecourt and will always cherish this spot.

[Caption:] Aviator’s View of Imecourt, Where Pittsburghers Fought. Large picture shows town and surrounding farms, pitted with shell holes. Single cross marks building hit by shell while soldiers were asleep inside, but in which none was hurt. Two crosses mark spot where Pittsburghers checked a German counter-attack, and three crosses the location of another fierce fight. The portraits are, from left to right, Col. W. H. Waldron, chief of staff of the Eightieth Division; Maj. Gen. Adelbert Cronkhite, then in command of the Eightieth Division, but now head of the Eighth Army Corps, and Brig. Gen. Lloyd M. Brett, commander of the One Hundred and Sixtieth Brigade.

- Charles J. Doyle, “Field Where Home Boys Lie Photographed,” The Pittsburgh Gazette Times, Sunday, February 9, 1919, page 47 (section 6, page 5). Google News Archive (https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=mG1RAAAAIBAJ&sjid=BGgDAAAAIBAJ&pg=2431%2C1364060 : viewed 2 January 2020).

- Photo from Dennis Stewart, MyHeritage.com, Robert M. Stewart Family (https://www.myheritage.com/site-148784861/robert-m-stewart-family : Downloaded 23 June 2016), Thomas Russell Stewart.

- François Depaix, e-mail to Mike Voisin, 13 June 2019, citing Raymond L. Thompson Papers, D.172, University of Rochester and the River Campus Libraries (https://rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/finding-aids/D172), Box 5, Reconnaissance Map and Aerial Photographs No. B1498 B1531, October 23, 1918, US-1AC-SQ1-B1530.

- Donnie Johnston, “Mitchells Presbyterian set to celebrate 150 years in Clupeper,” (https://www.starexponent.com/news/mitchells-presbyterian-set-to-celebrate-years-in-culpeper/article_0068899d-b48c-5e4f-bcf6-11ff2a0acb09.html : downloaded 22 September 2018), 10 October 2017.

- Diana Mazzella, “The Soldiers of World War I,” (https://magazine.wvu.edu/stories/2018/11/29/flashback-the-soldiers-of-world-war-i : downloaded 3 January 2020), citing West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries.

- American Battle Monuments Commission. 80th Division: Summary of the Operations in the World War. United States Government Printing Office, 1944, page 40-41. “The 3rd Battalion, having reached Imecourt, sent Companies L and M to the northern edge of the town. They entered the fight to the left of Companies F and H.”

- See blog post “Someone Will Remember For You,” 2 November 2018.

- The University of Texas at Austin, University of Texas Libraries, Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, (http://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/ww1/index.html : downloaded 19 November 2019), citing American Battle Monuments Commission, “Summary of Operations in the World War,” 1944, map 80th Division, Meuse-Argonne Offensive, October 23 – November 8, 1918.

- Larry R. Kephart, “Diary of William A Livergood. A tale of a soldier who served in the World War in France,” (http://www.laroke.com/larryk4674/2001/poppop.htm : downloaded 31 Oct 2018), citing Howard C. Spencer, photographer, 305th Engineers, 80th Division.

- Photographs taken by the “Griffin Group,” of areas occupied by American Troops during World War I combat operations, 1918 – 1919, National Archives Catalog, (https://catalog.archives.gov/id/532280), also AEF GRS Data_WFL1 (http://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=d16223d89fb242ada81d9c886d607ba5), “AM796-80 Immecourt 299.7-289.1 2-23-19,” taken February 23, 1919.

- François Depaix, e-mail to Mike Voisin, 10 November 2018, citing Photographs taken by the “Griffin Group,” of areas occupied by American Troops during World War I combat operations, 1918 – 1919, National Archives Catalog, (https://catalog.archives.gov/id/532280), also AEF GRS Data_WFL1 (http://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=d16223d89fb242ada81d9c886d607ba5), “AM802-80 Immecourt – Sivry Road 317th Inf. P.C. 299.7-289.9 2-26-19,” taken February 26, 1919.

- Major Charles Rossire, Jr., “A Brief Diary of the 319th Inf.,” With a Short Foreword by the Author, an article in “The Service Magazine,” Volume 4, Number 4, February-March 1923, pages 7-10. 80th Division Veteran’s Association (https://www.80thdivision.com/blueridge_wwi.html : viewed September 6, 2018).

- American Battle Monuments Commission. 80th Division: Summary of the Operations in the World War. United States Government Printing Office, 1944, page 40-41. “The 3rd Battalion, having reached Imecourt, sent Companies L and M to the northern edge of the town. They entered the fight to the left of Companies F and H.”

- Larry R. Kephart, “Diary of William A Livergood. A tale of a soldier who served in the World War in France,” (http://www.laroke.com/larryk4674/2001/poppop.htm : downloaded 31 Oct 2018), citing Howard C. Spencer, photographer, 305th Engineers, 80th Division.

- American Battle Monuments Commission. 80th Division: Summary of the Operations in the World War. United States Government Printing Office, 1944, page 40-41. “A detachment of the 305th Engineers, at work repairing this road [Imécour-Sivry road], had previously been driven off.”

- François Depaix, e-mail to Mike Voisin, 10 November 2018, citing Photographs taken by the “Griffin Group,” of areas occupied by American Troops during World War I combat operations, 1918 – 1919, National Archives Catalog, (https://catalog.archives.gov/id/532280), also AEF GRS Data_WFL1 (http://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=d16223d89fb242ada81d9c886d607ba5), “AM795-80 Ruined Chateau Immecourt 299.7 – 289.4 2-23-19.”

- War Department. Office of the Quartermaster General. Cemeterial Division. “Initial Burial Plats for World War I American Soldiers, 1920 – 1920.” Record Group 92: Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774 – 1985. National Archives Catalog (https://catalog.archives.gov/id/12007376 : downloaded 27 May 2019), 1919-3/15/1922.

- François Depaix, e-mail to Mike Voisin, 10 November 2018, citing Raymond L. Thompson Papers, D.172, University of Rochester and the River Campus Libraries (https://rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/finding-aids/D172), Box 5, Reconnaissance Map and Aerial Photographs No. B1498 B1531, October 23, 1918, US-1AC-SQ1-B1525.