Lt. Col. Ashby Williams

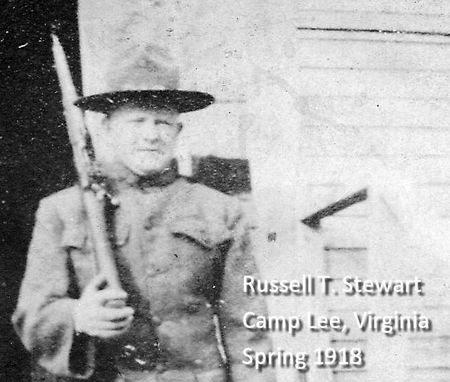

I must admit I was not very familiar with World War I history. I had studied it in school history classes, watched the old movies and read a couple books on the subject. I never really appreciated the courage and bravery of those who served in that war until I investigated the life of my mother’s uncle, Private First Class Russell Stewart. He served in Company M of the 319th Infantry Regiment, 80th Infantry Division. He died at the battle of the Meuse-Argonne on November 2, 1918, just as the war was ending.

In reading the relevant regimental and divisional accounts of that battle, I found the most interesting and moving account of all. It was written by Lieutenant Colonel Ashby Williams (1874-1944)1 in his book, “Experiences of the Great War” (Roanoke, Virginia: The Stone Printing and Manufacturing Company, 1919). He started out as commander of Company E, 320th Infantry and was promoted to battalion commander, with the rank of Major, over Companies A, B, C and D, of the 320th. Although he was an officer, he endured only slightly better conditions than his men. He describes in great detail the experience of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

The 320th and 319th were in the same brigade, the 160th, and undoubtedly shared the same locations, movements and conditions. Therefore his is probably the closest description of what my granduncle experienced. I have included here the most poignant and eloquent passages from Lt. Col. Williams’ book. His words describe the indescribable horrors of existence and death in the trenches. It is something the world often forgets, as I did, in my generation. But now I remember.

Men Like These Never Turn Back

In preparation for the first phase of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the 80th Division made its way to the front lines. This happened during the night of September 25 and the early morning hours of September 26. It would lead the attack at 5:30 that morning. What Major Williams describes here for the 320th is undoubtedly what Russell Stewart in the 319th also experienced.

…I ordered the companies to fall in on the road by our area preparatory to marching out of the woods. They got into a column of squads in perfect order, and we had proceeded perhaps a hundred yards along the road in the woods when we came on to one of the companies of the Second Battalion which we were to follow that night. We were held there perhaps forty-five minutes while the Second Battalion ahead of us got in shape to move out. One cannot imagine the horrible suspense and experience of that wait. The Boche began to shell the woods again. There was no turning back now, no passing around the companies ahead of us, we could only wait and trust to the Grace of God.

We could hear the explosion as the shell left the muzzle of the Boche gun, then the noise of the shell as it came toward us, faint at first, then louder and louder until the shell struck and shook the earth with its explosion. One can only feel, one cannot describe the horror that fills the heart and mind during this short interval of time. You know he is aiming the gun at you and wants to kill you. In your mind you see him swab out the hot barrel, you see him thrust in the deadly shell and place the bundle of explosives in the breach; you see the gunner throw all his weight against the trigger; you hear the explosion like the single bark of a great dog in the distance, and you hear the deadly missile singing as it comes towards you, faintly at first, then distinctly, then louder and louder until it seems so loud that every thing else has died, and then the earth shakes and the eardrums ring, and dirt and iron reverberate through the woods and fall about you.

This is what you hear, but no man can tell what surges through the heart and mind as you lie with your face upon the ground listening to the growing sound of the hellish thing as it comes towards you. You do not think, sorrow only fills the heart, and you only hope and pray. And when the doubly-damned thing hits the ground, you take a breath and feel relieved, and think how good God has been to you again. And God was good to us that night—to those of us who escaped unhurt. And for the ones who were killed, poor fellows, some blown to fragments that could not be recognized, and the men who were hurt, we said a prayer in our hearts.

Such was my experience and the experience of my men that night in the Bois de Borrus, but their conduct was fine. I think, indeed, their conduct was the more splendid because they knew they were not free to shift for themselves and find shelter, but must obey orders, and obey they did in the spirit of fine soldiers to the last man. After that experience I knew that men like these would never turn back, and they never did.2

There is No Glory and No Flying of Flags

The battle of the Bois des Ogons was the second phase of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive for the 80th Division. It happened from October 4th through 12th, 1918. And on October 12th both the 319th and the 320th were relieved by other units. The regiments made their way back from the front lines across territory they had just fought through. Major Williams finally had time to reflect on what just happened. He expressed that horror.

As I passed along the weary way that morning, I mused upon the great conflict in which we had taken part. I had no figures at hand, of course, because there had been no time for figures, but I knew my losses had been heavy and I knew also that in the three days of constant fighting we had penetrated a distance of three kilometers into the great third German main line of defense, and had inflicted heavy losses in killed, wounded and prisoners upon the enemy and had taken many of his guns. This was indeed some satisfaction, and it was also some satisfaction to be alive and unhurt; but on this morning, I think, sorrow was the uppermost feeling of my heart. Up in the line, with the responsibility of a battalion in the presence of a determined enemy, there was no time to think of men and men’s feelings and sorrows, and I thanked God for that many a time, but now that the great responsibility had been removed, a reaction set in, and I thought long upon the sorrow and suffering of those who had been maimed, perhaps for life, and of my brave boys who had made the supreme sacrifice for their country and were lying dead upon the hills behind me. There was no glory in such thoughts as these. Indeed, there is no glory in the savage struggle of man against man, with its bloodshed and its suffering and death and all that, to one who takes part in it; there is only the horror of it; the glory is for those who view it from afar in a glamour of unreality. There is no glamour in scenes of that sort, no marching to the strain of song and music, no flying of flags, no exaltation; but tired in mind and body from the long night march, or exhausted from loss of sleep under the horror of bursting shells and poison gas, and haggard from no disposition to eat the hard bread or the cold, canned stuff, or any other food, men go out to take a chance with death, stimulated alone by the excitement of danger and death and the deafening noise. Under the stimulus of the conflict their haggard minds are deaf to the simple sorrows and sympathies of man; but when the strain is removed, reaction sets in and they become again mere men with sympathies and sorrows and all the kindred feelings that God has placed in the heart. The presence of death brings one to the consciousness of his own infinitesimal self; there is no pride of heart, no self-exaltation there; relief brings out a heart of gratitude to God and of sorrow for man.3

Such Horrors as These

I shall quote one final passage from Lt. Col. Williams. His haunting words give a true sense of what happened there.

FootnotesIt is indeed a peculiar sense of pride and sorrow that comes over me as I contemplate this list of men who were killed or wounded in the great action above Nantillois and of those brave men who fortunately passed through it unharmed. But retrospect robs the three days’ battle of some of its most appalling aspects. Even now I am not able to feel the real horror of it, and I never have been able to describe it as it really was, nor has any one been able to do so: and no one, therefore, except the man who has been through it will ever be able to understand the anguish of mind and body, the priceless sacrifice of that three days of battle. We can now, in hazy retrospect, sitting before a cheerful fire in a comfortable billet, think and speak of the soldier’s body, emaciated from fatigue and from the lack of sleep and food, and indeed, from the lack of desire to sleep and the appetite to eat, and of all the night vigil full of anxious waiting in the cold, damp, shell hole for the dawn, not knowing but what the next horrible, whining thing will tear him into a million pieces; of the anguish of dying comrades tugging at the heart—we may think of these things and many other things now, but they are merely thoughts; time and circumstances have clothed them in a filmy haze of mere dulled recollection, stripped of all their horrible reality, and we shall never see nor feel it all again until fatigue through the day and night actually brings exhaustion to the body, until the nostrils are filled with the stifling, stinking, poisonous gas; until the body shivers and shakes in the cold, damp wind, and broken steel whines about the head, and life hangs by a thread—until we suffer the actual physical pangs of those horrors again, the days that I have spoken of will be a mere memory. Indeed, God is to be thanked that time dulls the memory of such horrors as these.

And yet, no matter how much of the horror time may efface, neither time nor circumstance, nor any other thing, can efface or lessen the sense and feeling of the inextinguishable debt that the people of America owe to those brave and heroic men who passed through that three days of hell on earth, plodding and wading through the third main German line of defense, offering indeed their very bodies, their very lives, that liberty and the civilization of the West might live upon the face of the earth. And there was nothing spectacular about those men; there was, with them, no beating of drums, no unfurling of banners, no loud noise, no mere trifling sacrifice of some small comfort or luxury of life; they went with their very bodies to meet the lead and the steel of the enemies of their country, and they tore down his strongholds of defense, and, with their very hands, they captured him and they killed him, and compelled him to capitulate and bring peace again to a troubled world; this is what they did and no word from me can add to the glory of their deeds.

Any man may be proud to find his name recorded here. I have often thought that the men who passed through those three days of battle should have some insignia as a mark of distinction among their fellows in the world, but that is not essential. Those men have indeed achieved for themselves a glory which no army or government can by a mere fiat add to or take from one jot or tittle and it should be a sufficient honor for any man to be able to say, “I went over the top at the Bois des Ogons on October 9th.”4

- Jim Tipton, Find A Grave (http://www.findagrave.com/: Downloaded 16 August 2016), John Ashby “Ashby” Williams, Sr (1874-1944), Memorial 64601385.

- Ashby Williams, Experiences of the Great War (Roanoke, Virginia: The Stone Printing and Manufacturing Company, 1919), pages 78-79

- Ashby Williams, Experiences of the Great War (Roanoke, Virginia: The Stone Printing and Manufacturing Company, 1919), page 137

- Ashby Williams, Experiences of the Great War (Roanoke, Virginia: The Stone Printing and Manufacturing Company, 1919), pages 154-155