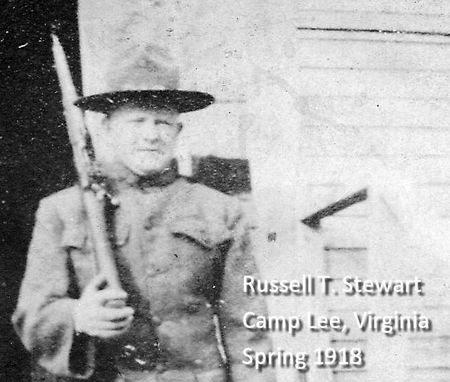

Corporal Arthur Nelan Pollock served in Company F, 320th Infantry Regiment, 80th Infantry Division during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in World War I. Amazingly, he kept a diary. It so happens he got separated from his regiment and became attached to the 319th Infantry. This was the same regiment in which my granduncle Russell Stewart served, as I describe in a previous post.

It is enlightening to read Corporal Pollock’s account of the battle. Since both men were then in the same regiment, this is very likely what Russell Stewart also experienced. Here is an excerpt of Corporal Pollock’s account from September 26 to October 2, 1918. It was originally published in the Pittsburgh Press, April 20, 1919 and continued on May 18, 1919. This excerpt was transcribed by Lynn Beatty and the full text is found at the Allegheny County, Pennsylvania USGenWeb.1

FootnotesAt 5:030a.m. on Sept. 26, was the ‘zero hour.’ The noise made by the cannon and machine guns behind us was terrific. You couldn’t hear the man next to you, but then he was about 15 feet away in this combat formation. The fog and smoke was so dense, too, that one could hardly see the next man although the sun was slowly coming up. Soon after we started Sergt. Halsey was shot in the neck and spit the bullet out of his mouth, dying later. In the confusion the smell of smoke and powder was mistaken for gas and gas masks were put on.

As we charged down the hill through the smoke, fog, and barbed wire entanglements with our masks on, we soon found ourselves in the cellars and ruins of buildings which the retreating Huns had left burning. Our squad had become detached from the rest of the company. After removing our masks we attempted to locate our company. Hearing familiar whistles to our right and ahead of us we double-timed it in that direction and attached ourselves to Co. C of the Three Hundred and Nineteenth infantry which was in the front line of assault. So far our progress had all be down hill, and now as we charged up hill the fog lifted and we could see the work our artillery was doing. The whole side of the hill was filled with shell holes, some 15 feet in diameter and nearly as deep. Barbed wire entanglements had been torn all to pieces and trenches and dug-outs blown up.

IT WAS UP-HILL WORK

In spite of the great noise made by our artillery in the rear we could hear the German machine guns in front of us, and advanced up the hill by jumping from shell-hole to shell-hole. Sometimes the shells would destroy the home of a jack rabbit, and how he would go jumping across No Man’s Land. Pretty soon a German popped up out of a trench ahead of us with his hands up and yelled ‘Kamerad.’ As no one fired at him he came toward us asking which way to go. Someone behind me told him New York was back in the rear, and away he went in that direction on the double, hands up all of the time.

I wasn’t advancing very fast, for the Jerries must have seen my automatic. Anyway when I wasn’t in a shell-hole they were making it pretty warm for me and the bullets were singing around my helmet at a great rate. Finally I made a dash the rest of the way up the hill and into their trench. There they were, two youngsters, one looked a lot like Frank Brosius and neither one looked a bit older. Both were crying ‘Kamerad.” The German machine gun is a water cooled affair and we had come upon them so swiftly, they hadn’t had time to connect it up but had fired it until it was so hot it wouldn’t fire anymore.

I searched my prisoners and as they had no arms I destroyed their machine gun and showed them the way back to the cage. You can understand why a guard is not sent back with two or three men when I tell you that about ever three or four hundred yards there were lines of soldiers following the front line. Over on my right there was a great deal of cheering and yelling. The boys had captured a dug-out in the same trench and 27 ‘square-heads’ as we called them. They were filing out to be searched and started to the rear; some old men, some boys, but all appearing to be well-fed. A lot of ammunition and some German grub were captured in the trench. I might say right here that later reports showed that 1,500 prisoners had been captured in the first half hour of the battle. This is a pretty good record considering that we occupied only two kilometers of the one hundred kilometer front.

Then we went ‘over the top’ again and forward to the next German trench, leaving the ‘moppers-up’ to get all the Germans out of the dug-outs and take captured material back. The machine guns continued to fire on us and quite a few of our comrades were being wounded, but there were a great many of dead and wounded Germans lying around also. Before we reached the next trench a long string of Jerries came out toward us with hands up; some were laughing and seemed to think the war over as far as their fighting was concerned. They handed our boys their watches, knives, money, cigarets, etc., as they filled up to be searched. A daschund dog came with them answering the name of ‘kaiser’ and followed the ‘squareheads’ back to the prison camp. Here is where we got the name of ‘not knowing when to stop.’

INTO THEIR OWN BARRAGE

In the excitement of taking prisoners we had charged forward too fast and were ahead of our own barrage, in other words ‘between two fires.’ Quite a few of our own men were badly mangled here. Not being with my own company, I didn’t know any of the wounded, and it was hard to leave them, but for our own safety we were ordered to the right into some trenches. The doctors, first-aid men, and Red Cross, followed right up and took care of the wounded. Rocket signals were sent up and our airplanes which were flying overhead, hurried back to the artillery and soon the shells were tearing great holes in the earth ahead of us again. I was now with Co. A, Three Hundred and Nineteenth infantry.

As we advance again we came to a swap where the engineers were putting up a pontoon bridge. After crossing this we ran into a machine gun fire from a woods. Locating a machine gun and attempting to flank it, I found myself with Co. G of the Three Hundred and Nineteenth (Karl Hewitt’s company.) I connected myself to the company and was assigned to Corp. Shafer’s automatic squad. We soon captured the machine gun and advanced into the woods, and to dugouts where we spent the early part of the night. On our left 25 or 30 Germans started toward us across an open field with their hands up. Some of the foreigners in the company opened fire on them and they fell back and gave us an awful battle. Later in the evening the German artillery got our rand and airplanes dropped bombs on us. Al told we spent a very uncomfortable night to say the least. (Corp. Shafer is a Wilkinsburg boy, and worked at Hall’s roundhouse on the Union railroad.)

Soldiers killed or dying from being hit by shrapnel turned a horrible yellow color, but those hit by machine gun bullets turned blue.

On this afternoon when Jerry was making things warm for us our artillerymen sent over some liquid fire shells which set fire to the woods which the Huns were holding, and with the officer’s field glasses, we were able to see them retreating over the hills.

On Sept. 27, at 4 a.m. (before daylight) we combed the woods which seemed to be a lumber camp or source of wood supply for the German army. Without a barrage we conducted a raid on a little town which the Germans had used as a hospital, and which as they retreated they left burning. Passing through the town we went up a hill through another woods, then down the other side of the hill to the edge of the woods overlooking the Meuse river. The city of Dunn sur Meuse could be seen in the distance. In the last woods we met several machine guns and captured them. We had reached our objective at about 10 a.m. but the Three Hundred and Twentieth infantry on our left had met with stiff resistance and had not advanced as far as we were.

IN THE ENEMY’S QUARTERS

We dug bivrys [sic] big enough to shelter us from machine gun fire and Company headquarters were established in what had been a German officer’s quarters. Her there was glass in the windows, lace curtains, a desk, a table, a big leather Morris chair, and a ‘regular’ bed in another room. The rooms were wired for electric lights. While here we were shelled quite a little. They used gas on us in the woods. This little bungalow occupied by Company headquarters had also been a first aid station. We spent the night here, another company relieving us in the morning and at 6 a.m. we moved back to support trenches on top of the hill.

On Sept. 28, the Three Hundred and Twentieth on our left, had still not reached their objective and we were in a pocket and being shelled from three sides, getting quite a lot of gas. German airplanes fired on us with machine guns but our planes drove them off. Towards night to make matters wore [sic] it started to rain and rained all night. We were in a shallow trench and had to stay down on account of the flying shrapnel and machine gun bullets. The trench was soon a creek and we were soaked. German planes flew over us again, not a hundred feet above, firing their machine guns directly at us.

On Sunday morning, Sept. 29, about 5 o’clock we were relieved and started on our march back. Having no water in my canteen, it was on this march that I got so thirsty and drank from a shell-hole. I had given nearly all of the water in my canteen to wounded men. It was very risky business to drink water out of a shell-hole, as the rain might have filled the hole made by a gas shell which poisons the water.

On our way back we saw great quantities of ammunition and rifles and even heavy artillery that had been captured from the enemy. Some of this artillery had already been turned around and our gunners were firing German ammunition from German guns. Our wounded had been taken care of and the dead were being buried. In some places there were great heaps of dead Germans. A great number of horses were dead along the roadside, most of them having been gasses – some of them even had gas masks on, probably put on too late. The boys called these horses and mules ‘more bully beef.’ We passed several German airplanes that had been brought down and saw lots of terribly mangled soldiers when we passed a field hospital. Further back we met some of the little French whippet tanks, going like the dickens to the front. They were probably making 15 miles per hour and are about the size of a Woods Mobilette with two men in each. We also me auto trucks of ammunition and rations, and artillery was being brought up closer to the front.

About noon we stopped in a woods and the kitchen wagons came up, but before we could get started to eat ‘Jerry’ commences shelling the woods. About the same time we received word (by airplane, I believe) that the Seventy-ninth division in front of where we were, was being driven back. There certainly were a lot of wounded soldiers being brought back. Without waiting for dinner and as tire as we were we turned around and started forward to help our comrades. We had progressed only a short distance when another plane flew over us and dropped a message telling us the Seventy-ninth division had overcome the resistance and was again advancing. Then we had our dinner by the roadside, the first warm meal for four days.

We marched by reserve trenches at Cuisy, where Corp. Shafer, Private Books and myself dug a bivry and tried to sleep. We had just finished our little dugout when it commenced to rain. All night long the army mule rent the air with his unearthly braying. (The warm dinner consisted of stew, tomatoes, coffee, bread, jam and sugar.)

On Sept. 30 we were moved to another part of the trench and made a new bivry and a fire. For dinner we warmed up some canned roast beef and bacon and made coffee. In the afternoon I cleaned up my equipment and rifle and at 6 p.m. supper was served from the kitchen, which was now located in the trench. We had roast beef, beans coffee, doughnuts, bread, syrup and sugar.

Oct. 1 – At 2 p.m. the men who had been lost came back to the company. Breakfast at 8 a.m., consisting of bread, bacon and coffee. In the forenoon I cleaned up for inspection, also washed my feet and we had foot inspection. For dinner at 2 p.m. we had fresh beef stew, bread, jam, coffee and sugar. In the afternoon the first mail came since Sept. 22, via ‘G’ company. After supper at 6 p.m. Shafer and I had a long talk about Wilkinsburg.

Oct. 2 – I was on gas guard from 1 to 2:30 a.m. The Germans were throwing shells over our heads at artillery trenches on the hill behind us. Breakfast. Was placed again on gas guard from 8:30 to 10 a.m. We could see and hear the great shells going over our heads and see them tearing great holes on the other hill. Dinner was good. Steak, gravy, potatoes, bread, Karo, coffee. About 3 p.m. I located my own outfit (Co. F, Three Hundred and Twentieth infantry) in the same reserve trenches about two kilos to the right. The boys made quite a fuss over me and seemed glad to see me again. Corp. Cast and Corp. Scheidor in particular seemed glad that I hadn’t been wounded or taken prisoner.

- Pennsylvania, USGenWeb Archives, Allegheny County, Military, World War I, (http://www.usgwarchives.net/pa/allegheny/military/wpa-ww1/chapter-16.htm : 3 August 2016.)