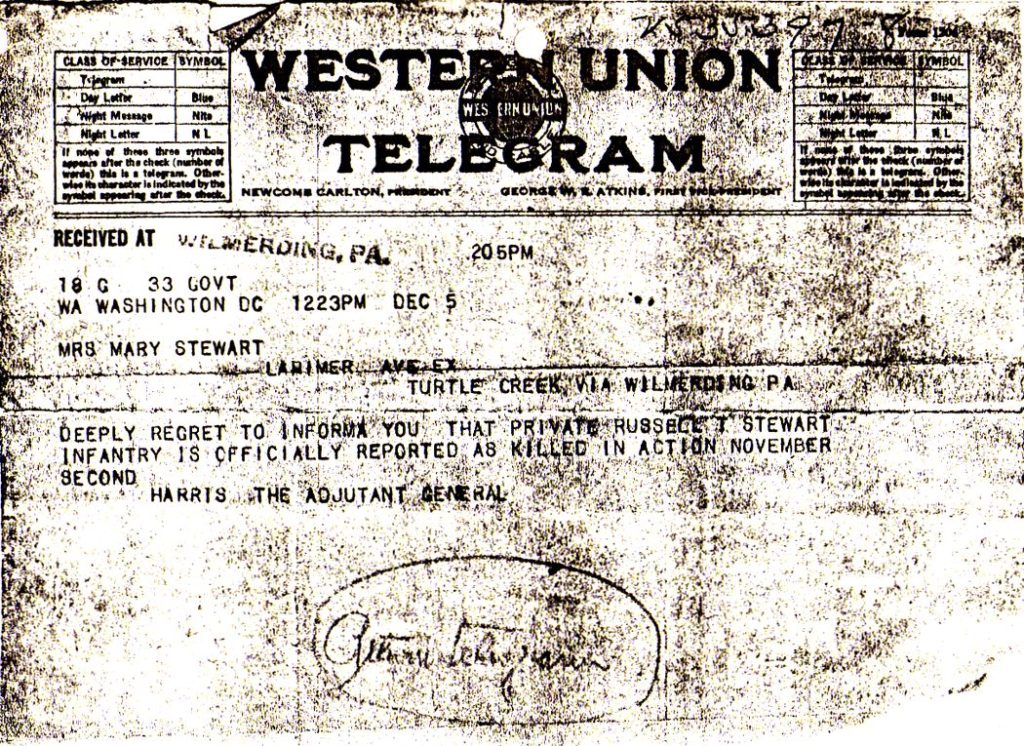

My granduncle Russell Thomas Stewart was my maternal grandfather’s younger brother. In a family tree published by my second cousin, Robert M. Stewart, there is a somber copy of a telegram addressed to my great-grandmother, Mary (McKee) Stewart, and dated December 5, 1918.1 It was news that her son Russell Stewart was killed in action November 2, 1918.

Finding no other information, I decided to investigate the short life of my granduncle, who I had never heard about. I was able to find a little more about him, but his story is mostly the tragedy of World War I and the sad ironies of its end.

Early Life

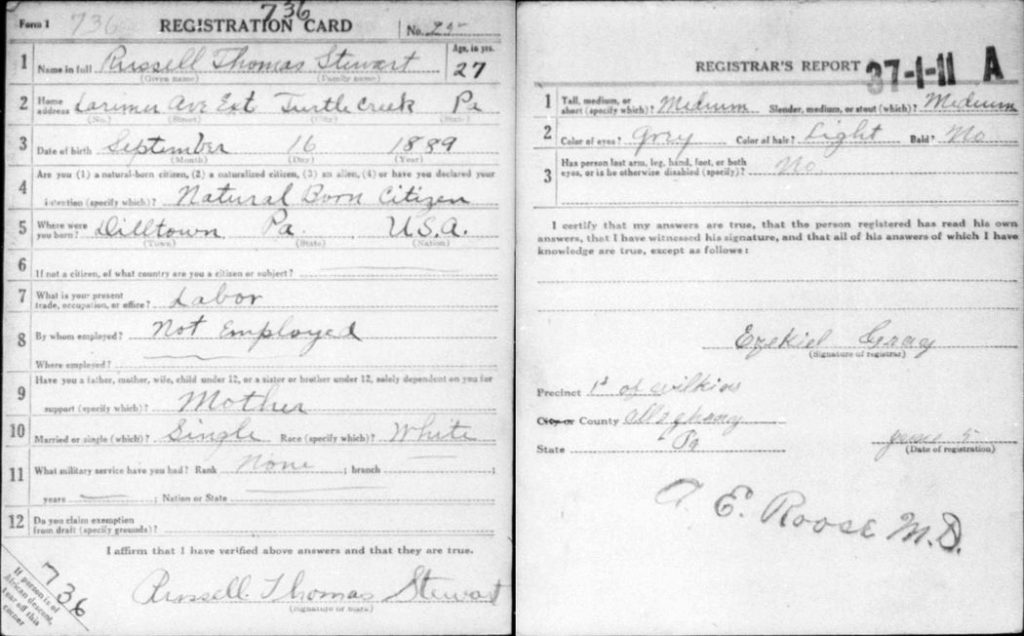

According to his draft registration, Russell was born September 16, 1889 near Dilltown in Indiana County, Pennsylvania. He was a son of John Galbreath Stewart and Mary (McKee) Stewart. His father died at the young age of 39 in 1894, when Russell was 5. His mother then moved to Turtle Creek, a suburb of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where the family is listed in the 1900 Federal Census.2

Russell went on to marry Grace Davis December 24, 1909 in Wellsburg, West Virginia just across the state line, and coincidentally, where my grandparents were married less than a year later.3 They had two daughters, Violet Mary Stewart, born December 4, 1910, and Anna Mae Stewart, born January 6, 1913. Sadly, Violet died of pneumonia at age 2 on March 10, 1913.

Russell registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, at the age of 27.4 He lived in Turtle Creek, and was unemployed. He was medium height, medium build, with gray eyes and light hair.

A Mysterious Twist

Interestingly, Russell indicated he was single. What happened to his wife and family? And, why was the telegram reporting his death sent to his mother rather than his wife? Grace and Russell apparently divorced sometime between 1913 and 1916. Grace married William Lincoln Dyer on July 24, 1916 in Ohio. She took custody of their daughter Anna and the family eventually settled in Canton, Ohio. (See my subsequent post for details.)

Military Service

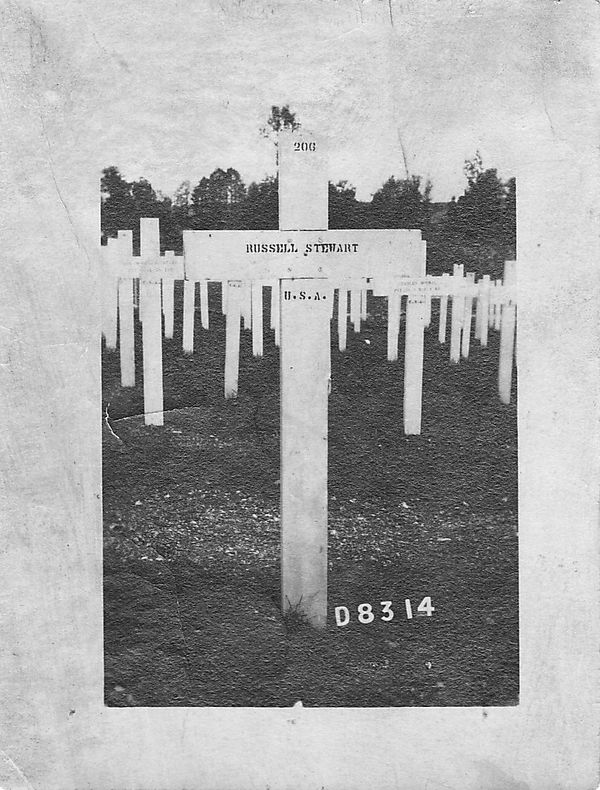

I found Russell’s grave and a picture of his grave marker. His is one of the thousands of marble crosses neatly aligned in a field in France.5 The marker indicates he served in the 319th Infantry Regiment, 80th Infantry Division. That was the clue I needed to learn about Russell’s final weeks.

The 80th Division was known as the “Blue Ridge Division” because most of the recruits were from the Blue Ridge Mountains of Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Virginia. The 319th Infantry in particular was composed mostly of men from Pittsburgh and surrounding Allegheny County, Pennsylvania.

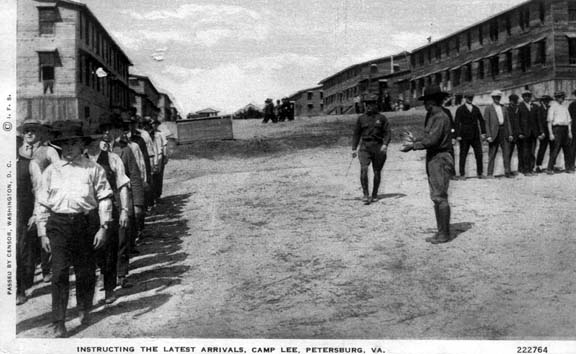

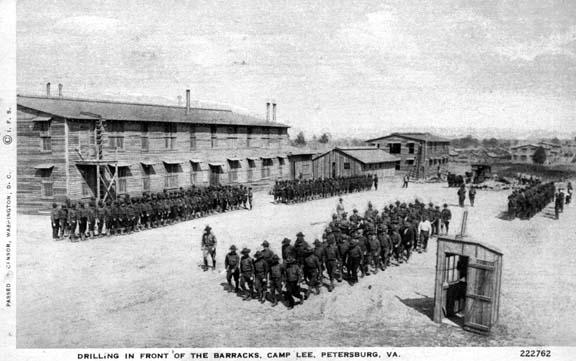

August 27, 1917. The 319th Infantry Regiment was created and preparations began at Camp Lee, near Petersburg, Virginia for the great influx of draftees. Camp Lee is today known as Fort Lee. The first 5% of draftees began to arrive September 6th. A large contingent arrived September 20th and the final group arrived October 6th. Russell was among the last of the draftees, at a time when Army uniforms were in short supply. Initially, he probably had to train in his civilian clothes and shoes.

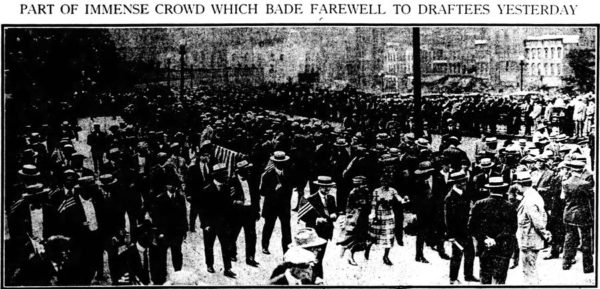

To see the draftees off, there were parades and cheering crowds at Pittsburgh train stations.6 By early November 1917, all companies in the 80th Division were up to strength.

Training continued at Camp Lee throughout the winter as weather permitted. In the spring, mock trenches were used to simulate actual conditions in France.

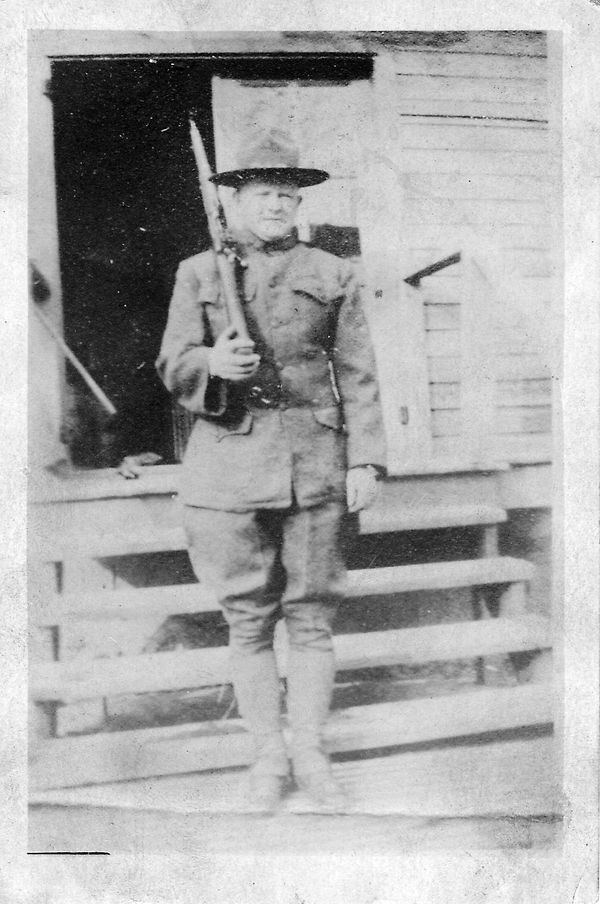

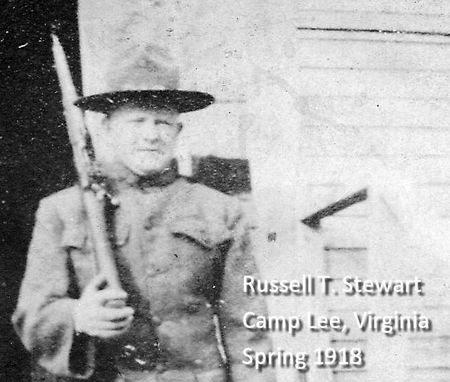

This is likely a photo of Russell Stewart taken at Camp Lee.7 To help identify it, I compared his face with that of his older brother, my grandfather John G. Stewart, taken about 1910. It does show a family resemblance.

Russell served in Company M of the 319th Infantry Regiment. Some, like Company F, documented their history, but I have not found a history of Company M. Not all companies in the regiment participated in the same operations. During battle it was possible for soldiers to get separated from their company and be temporarily attached to another company. Therefore I do not know precisely where Russell was, only the general area where the 80th Division, and the 319th Infantry in particular, was deployed.

Deployment

May 17, 1918. The Division was suddenly ordered to leave Camp Lee for Newport News and Norfolk, Virginia. They quickly boarded trains for these ports and during the night they boarded their ships. The next morning a convoy of ships sailed away amid cheering local crowds.

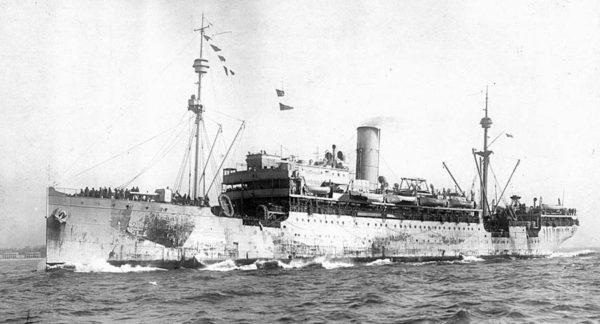

Russell sailed May 18, 1918 from Norfolk8 aboard the Zeelandia, a Dutch passenger ship converted for use as a troop carrier by the US Navy.9

The convoy was escorted by a Navy cruiser part of the way, and as they neared France, it turned back and a fleet of destroyers accompanied them. Soon they were under attack by up to seven enemy U-boats. The destroyers dropped depth charges and fired their guns as the men watched on deck. The U-boats fired torpedoes, but none of the convoy ships was hit. Shown here, a similar transport convoy is under attack by submarines.10

The convoy safely made port May 31st at St. Nazaire, France. On June 4th, Russell was promoted from Private to Private First Class. That was also the day they started their move inland. It was an arduous journey in cramped “40 hommes/8 chevaux” rail cars. These light “40 and 8” cars could carry 40 men or 8 horses. This was followed by days of long marches between several towns. The Division went to the British sector and trained under the direction of British instructors. They were sometimes close to the front lines.

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive

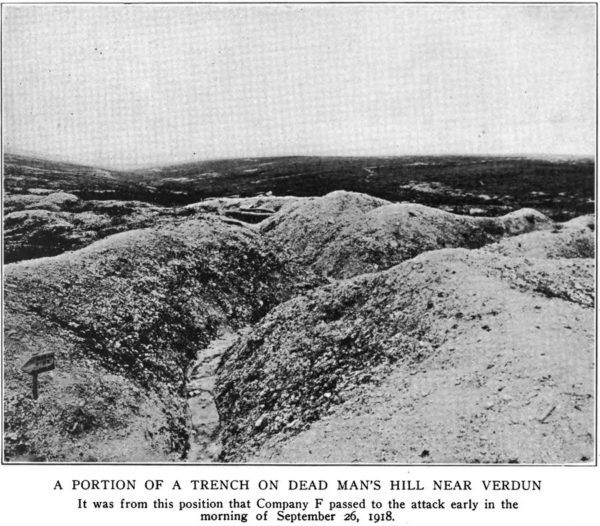

August 21st the Division was on the move south past Paris to the St. Mihiel salient west of Verdun. Now close to the front, the men had to quickly exit the train and take cover in the woods. The marches now were under cover of darkness to avoid detection by the enemy. Russell spent his 29th birthday camped near Bois-de-Vaux Warin and by September 25, his regiment was in position at Le Mort Homme (Dead Man’s Hill) near Bethincourt about 500 meters from the front line.

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive was about to begin. It happened northeast of Paris, near the border of Belgium, in three phases from September 26 to November 11, 1918.

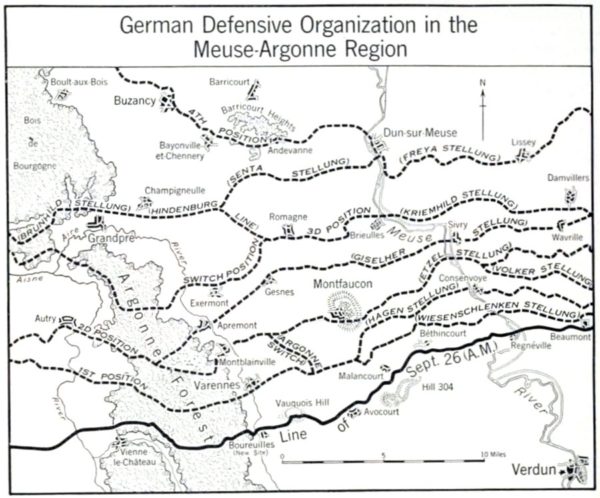

This map shows the complex and daunting system of German trenches that awaited our troops.11 Multiple successive fallback trenches were available to the enemy in case they had to pull back during battle. Advancing on such trenches was like a new attack each time.

The First Phase

September 26th began with an artillery barrage directed at the enemy from 1:00am until 5:00am. Next an intense barrage pounded for 30 minutes followed by a rolling barrage, where shells began exploding 100 meters further ahead, every 4 minutes. As the barrage rolled forward the 319th Infantry went over the top of their trenches and followed it. They passed through a swampy area without difficulty and reached their objective under light enemy fire. They pressed forward and reached a second objective.

Russell’s unit was held in reserve this morning, probably because it had already been active at the front line. On September 22 his battalion had relieved the 131st Infantry, 33rd Division. He was however sent out later in the morning:

About 10:30 a. m. Company M, 319th Infantry, was sent forward to support the 1st Battalion and took up a position extending from the southwest edge of Bois Jure across the open ground to Bois Sachet.12

At times the various companies could not determine their direction with certainty and this led to confusion. This was compounded by exhaustion. Some men had not slept for 60 hours.

For instance, ‘M’ Company was on the right of the third battalion and ‘I’ Company on the left when the advance began, but when the objective was reached, their positions were exactly reversed.13

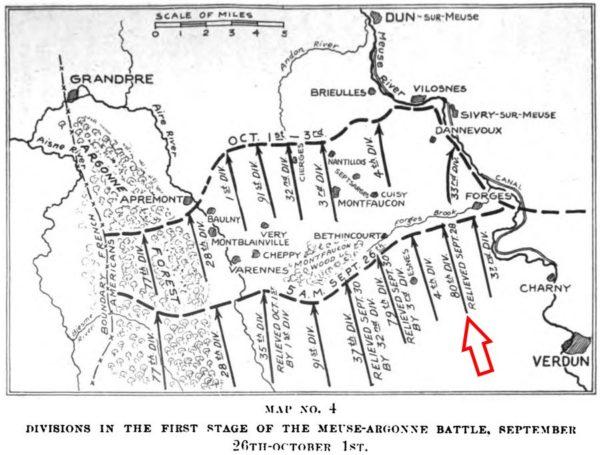

This map shows the position of the 80th Division at the start of the offensive.14

The next day the enemy began a heavy artillery bombardment. That was combined with periodic machine gun fire and snipers. They continued forward, but were eventually relieved by another regiment on September 29. They made their way in the dark early that morning, during a driving rain and by noon everyone was at a point 10 kilometers rearward. For a personal account of these days in battle, refer to the diary of Corporal Arthur Pollock. He and Russell Stewart were probably in close proximity.

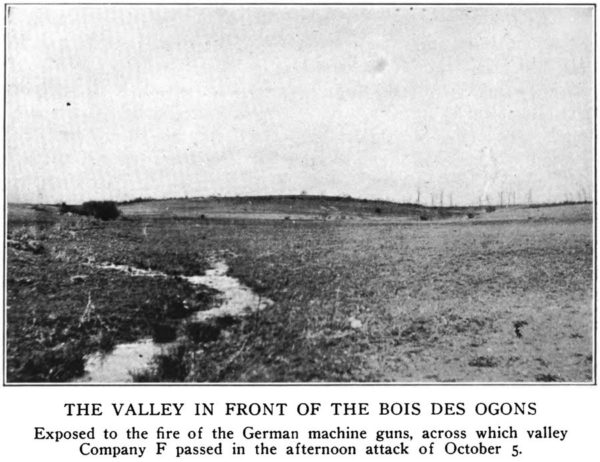

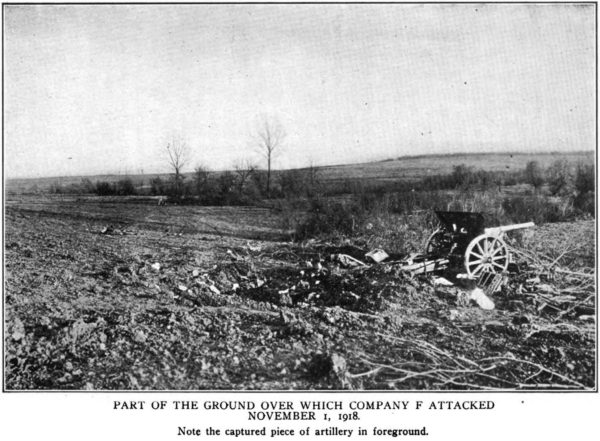

The battlefield views that follow were published in the history of Company F, 319th Infantry.15 Russell Stewart was probably in the same area as Company F and witnessed these very same views. However, these are “official” army photographs taken at a later date.

September 26th to September 29th: The 319th Infantry lost 63 killed, 26 died later of wounds, and 218 were wounded. Russell Stewart survived.

The Second Phase

On October 4th at 7:15pm, the 319th attacked Bois des Ogons (Ogons Woods). They were assisted by tanks, but could not hold their gains. Company F penetrated further into enemy lines, but finding no other units had advanced with them, they had to retreat, leaving nearly 70 men, most of whom were found by the enemy in shell craters the next morning and taken prisoner. Attempts to occupy the woods during the night were unsuccessful.

At 10:00am October 5th, the 319th was forced by heavy artillery fire to withdraw south of Bois des Ogons. The enemy’s high-explosive artillery fire, whizz-bangs, machine gun fire and gas attacks continued day and night. They wore gas masks most of the night. “Whizz-bangs” are light artillery shells that travel faster than sound. The men heard the whizz going by them before they could hear the bang of the cannon itself. They were especially scary because they came without warning.

On October 9th at 3:30pm the attack was renewed in what was described as the “wildest night” in regimental history.16 At times the advance was delayed, giving the enemy time to move between companies and direct fire between them.

…[Company] ‘M’ continued to advance, and some minutes later Captain Hickman sent a platoon to assist [Company] ‘K.’ The enemy, taking advantage of the halt on the left, infiltrated between ‘M’ and ‘K’ so that when the latter attempted the movement to the right, following the other companies, a murderous fire, which effectually prevented a further advance, was opened upon it.

… ‘I,’ ‘L,’ and ‘M’ Companies continued to advance without great difficulty, the enemy line being pierced, and proceeded north of the Cunel-Brieuelles road. Here Captain Egan directed Captain Hickman [commanding Company M] and Lieutenant Woodward with ‘M’ Company and two platoons of ‘L’ to clean up the village of Cunel, which they proceeded to do, capturing, possibly two hundred prisoners, including the personnel of two battalion headquarters—only about half of whom were ever conducted safely to the rear of the American line. The prisoners were guarded in the church while the village was thoroughly combed. One platoon of ‘M’ Company was sent back with the prisoners, the remaining platoons of the two companies proceeding northward toward the objective beyond the Bois Rappes…17

Companies M and L continued forward only to discover their own artillery was shelling the area, causing them to retreat. Then the enemy discovered their position and began shelling, trying to cut them off from reaching the American lines. Only 30 men from Company M returned and large numbers of other companies became lost and scattered in the darkness. However many returned and reorganized the next morning.

During several hours of the night Regimental Headquarters was not in communication with the three companies of the battalion, runners being unable to find them, and it was feared that the entire force had been cut off and captured behind the enemy’s front line.18

To the right of the 319th was the 320th Infantry. A battalion (four companies) of the 320th was commanded by Major Ashby Williams. From his perspective, the failure of the 319th to gain and hold Cunel that night caused severe hardship for his men.

I had been informed during the night by regimental headquarters that Cunel on my left front had been taken during the night by the 319th Infantry, and from this it was assumed of course that all the enemy’s positions in the 319th sector south of Cunel on my left had been taken also, because the 319th necessarily had to pass through them to take Cunel. As a matter of fact Cunel had not been taken, nor had the strip of woods south of that place on my left flank been taken. This erroneous information was based upon the fact that a part of the 319th Infantry, after passing over the Bois des Ogons on the night of the 9th, lost contact with the remainder of the outfit and had struck through the open country along the ravine south of Cunel and passed in the darkness on to Cunel, where some prisoners were taken and, as I am informed, a considerable number of the 319th also were lost to the enemy, and this detachment from the 319th (which, by the way, had taken a part of my “A” Company along with it) had withdrawn during the night back to the Bois des Ogons, leaving Cunel and positions south in full possession of the enemy. More over, the 4th Division, on my right, had not advanced out of the Bois de Fays. Therefore, my battalion, during its all-night fight through the woods, had driven a salient of six hundred meters in depth into the German lines in advance of the 319th Infantry on my left and the 4th Division on my right. So that when the barrage was laid down along the Cunel-Brieulles Road neither the 319th Infantry on my left nor the 4th Division on my right could follow it, because the enemy was between them and the barrage in their front and they could not reach the barrage.19

…On the morning of October 10th, therefore, I was attempting an advance upon information that my left flank was protected, but in reality it was completely exposed to fire…. When my advance began, therefore, my left flank companies had not gone two hundred yards north of the Cunel-Brieulles Road before, coming over the edge of the slope, they were exposed to a murderous machine gun fire [from] my left flank in the 319th Infantry sector. …It is needless to say that in the face of this murderous cross fire it was suicide to advance further in that flank, and it therefore became necessary for my left flank companies to withdraw into the woods just south of the Cunel-Brieulles Road.20

…I must not omit to say, however, on behalf of the 319th Infantry, that they had hard sledding, because I could see when the barrage of the morning came down our own artillery shells were falling short on some of the troops on their left flank and they were compelled to fall back to get out of it and not without casualties, but the barrage did not touch the strip of woods to the right of their sector…, which was the position so stubbornly held by the Boche and which had given that organization so much trouble.21

During September 30th to October 31st, the 319th Infantry lost 91 killed, 37 died later of wounds, and 467 were wounded. Russell Stewart endured all this, and survived yet again. He was either one of the 30 men in Company M to return, or he returned the next morning, or he was in the platoon that took prisoners rearward.

The regiment was relieved October 12th and made it’s way rearward for rest. Nearly everyone suffered some effect from poison gas. During the break, replacements arrived. The regiment was also trained to use the newly issued Browning automatic rifles. By October 22nd, the regiment was on the march again and deployed to La Chalade at the edge of the Argonne Forest.

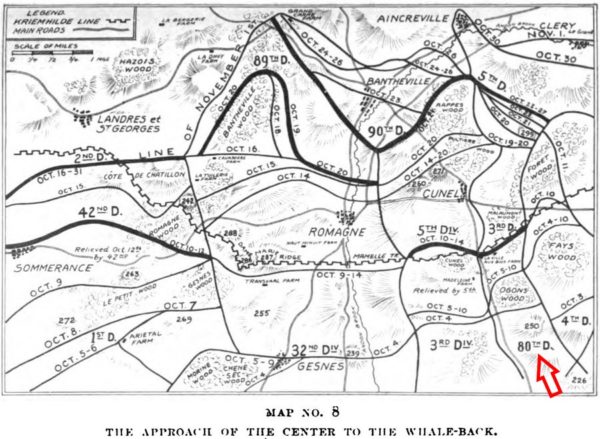

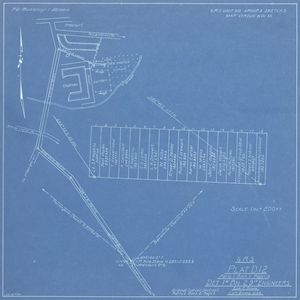

This map shows early October 1918.22 Note that Russell and his Company, Company M, made it to Cunel October 9th, well behind enemy lines, which were just north of Bois de Ogons on October 10th.

Actually Russell’s Company is alluded to in a monograph used by the Army to study the battle, published shortly after the war. It recognizes the importance of capturing the enemy by surprise.

… the 80th Division made a considerable gain so that at dark its troops were on the Cunel-Brieulles Road. Two companies filtered into Cunel itself, surprising the garrison and capturing them. The following day the 80th Division planned to continue its attack but the enemy’s fire broke it up before it got started.23

Ironically, Russell would later be buried only one mile from Cunel. Below is shown the ruins of the town as it looked in December 1918. Russell probably witnessed a similar view two months earlier.24

The Third Phase

On October 30th, the 319th marched to Apremont, where it waited until dark, then marched to positions near Sommerance. Here they spent all day and the night of October 31st under heavy enemy artillery fire, which included high-explosives and poison gas.

At daybreak November 1st, another rolling barrage began and the 319th moved forward to attack. They reached Imécourt, where they met stiff resistance. American artillery bombarded the area north of Imécourt and the enemy returned a counter-barrage. They continued forward just behind a rolling barrage and Companies F and H pushed 2 kilometers further to Sivry-les-Buzancy.

The 3rd Battalion, having reached Imecourt, sent Companies L and M to the northern edge of the town. They entered the fight to the left of Companies F and H.25

Russell continued to repulse enemy counter-attacks all afternoon and into the night. He survived another harrowing day. That night the regiment reorganized and prepared for another attack the next morning, November 2nd.

[A field order], issued at 1 a.m., November 2, ordered the 160th Infantry Brigade [Russell’s Brigade], plus the 317th Infantry and two companies of the division machine-gun battalion, to attack due west at 6 a.m. The assault was to be made by the 319th Infantry, from the general line Imécourt—Sivry, to the objective, the western edge of the wood about 1,500 meters east of Verpel. The attack was to be initiated by a standing barrage on the eastern and southern edges of the wood at 6 a.m. The mission of this phase of the attack was to clean out the divisional zone west of the line, Imécourt—Sivry.26

The Division history goes on to describe the attack:

The first phase of the operation was carried out by the 3d Battalion, 319th Infantry, plus Companies E and G. With four companies in the assault echelon and two in support, the attack was launched at 6:55 a.m., and moved west between horizontal grid lines 291 and 292, passing through the woods northwest of Imécourt without encountering resistance. The western edges of the woods were reached about 7:30 a.m. Patrols were sent to Verpel, Thénorgues and Buzancy by 8 a.m.27

Although the Division’s account indicates “no” resistance was encountered, the 319th Infantry’s account describes it as follows.

A reorganization was effected during the night [of November 1], and at 5:00 a.m. the regiment attacked towards the west, to clear the woods northwest of Immecourt. The enemy, whose machine gun fire had ceased about 4:00 a.m. was discovered to have abandoned the woods, but his artillery put down a heavy fire therein during the advance. Passing through the woods, the regiment halted and patrols were sent into Verpel and Buzancy, both towns being found free of the enemy.28

And more specifically, the history of Company F describes:

Early on the morning of the 2nd our barrage started up. It was falling close to our position and for safety the troops withdrew three hundred yards, later they advanced to the top of the hill and in a driving rain, started to dig in. The German shell fire added to the hardships. About 9.30 a.m. the 159th Brigade passed through our lines to take up the attack.29

A more detailed account was published after the war by Jennings C. Wise, who wanted to set the record straight, and give credit to General Lloyd M. Brett, commander of the 160th Brigade (Russell’s brigade). Brett acted quickly and on his own initiative to order the attack:

The operation was entirely successful. By 4 a. m. on November 2 the Three Hundred and Nineteenth Infantry had delivered its attack under the personal direction of Gen. Brett in exact accordance with the plan of those who designed it, clearing out the wood north of Alliepont, and sweeping westward north and in rear of Champineulle, Three Hundred and Fifteenth Machine Gun Battalion in position on the Immecourt ridge being utilized to cover the necessary changes of position and deployment of the infantry units. So soon as the pressure of the Three Hundred and Nineteenth Infantry was felt on his left flank the enemy vigorously pressed by the Three Hundred and Twentieth Infantry from the south, abandoned Champineulle and the Bois-des-Loges in turn, falling back rapidly in a north-westerly direction through Briquenay to the line Buzancy-Bar-Harricourt, which was already seriously threatened at Buzancy by the One Hundred and Fifty-ninth Brigade, which captured the town early on the morning of the third. Before noon the One Hundred and Sixtieth Brigade had taken Verpel and Thenorgues, and soon thereafter the Seventy-seventh and Seventy-eighth divisions were able to come into line abreast of the Eightieth, having passed through the once formidable positions of Champineulle and the Bois-des-Loges without serious resistance. By nightfall the entire line of the First Army had been rectified and brought up to schedule, so that it now extended from the Meuse near Clery due westward through Sivry-le-Buzancy to Barricourt. the Seventy-eighth, or extreme left division, having been squeezed out of the line. Contact with the French on the left near Germont was complete….30

Other evidence corroborates this account. First the casualty counts for the 319th Infantry for November 2 are higher than one would expect for an advance through the woods with “no” resistance. Second, the high command immediately praised General Brett via telegram the same day, November 2. Such praise was rare, and is unlikely for an attack with “no” resistance.

Telegram from the Commanding General, First Army Corps, 2 November 1918: “The Corps Commander is particularly pleased with the persistent, intelligent work accomplished by your Division today. He is further desirous that his congratulations and appreciation reach General Lloyd M. Brett, commanding your Brigade [160th], which has borne the brunt of the burden.”31

So Russell’s brigade bore the brunt of the attack, although this is not indicated in the Division history. The reason is alluded to by Thomas W. Hooper, who wrote a letter to the editor of the 80th Division’s veteran’s magazine after the war:

From our days in Camp Lee, it seemed that there was some sort of suspicion of the 3rd Battalion, 319th Infantry, [Russell’s battalion] which the writer has never yet been able to understand. Certainly, the credit for the part that this battalion took in the fighting has not been given it….

…As a matter of fact, when the two companies of [Capt. Rossier’s] battalion that advanced to the neighborhood of Sivry had left Imecourt, the Germans attempted a bit of a counter attack. The whole of the 3rd Battalion was thrown out around Imecourt and along the Imecourt-Sivry road to protect the left flank of those two companies. They held this position all during the night of Nov. 1 and 2.

The attack of Nov. 2nd, on the woods northwest of Imecourt was made chiefly, if not entirely, by the 3rd Battalion, 319th Infantry [Russell’s unit]. By Capt. Rossier’s statement, two companies of the 2nd Battalion were held in Sivry until that night, and if the other two companies of the battalion were in the advance of Nov. 2nd, I did not see them. It was the 3rd Battalion that immediately sent out the patrols. It is not the intention of these corrections to take any glory from a single man, but in the interests of truth they should be made.32

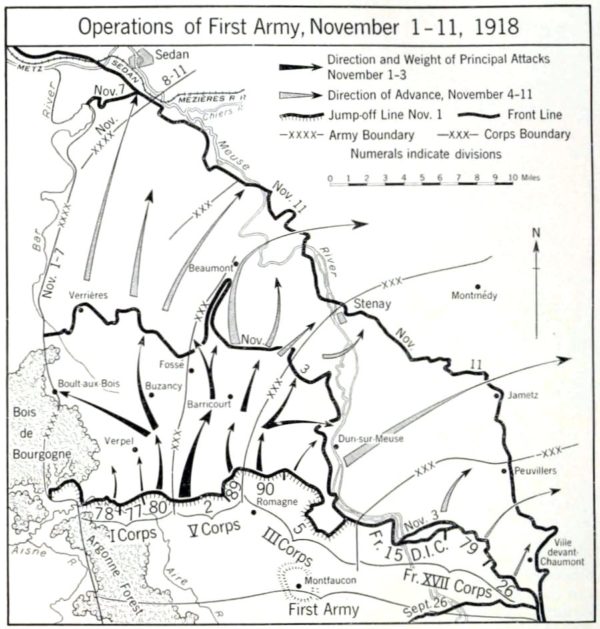

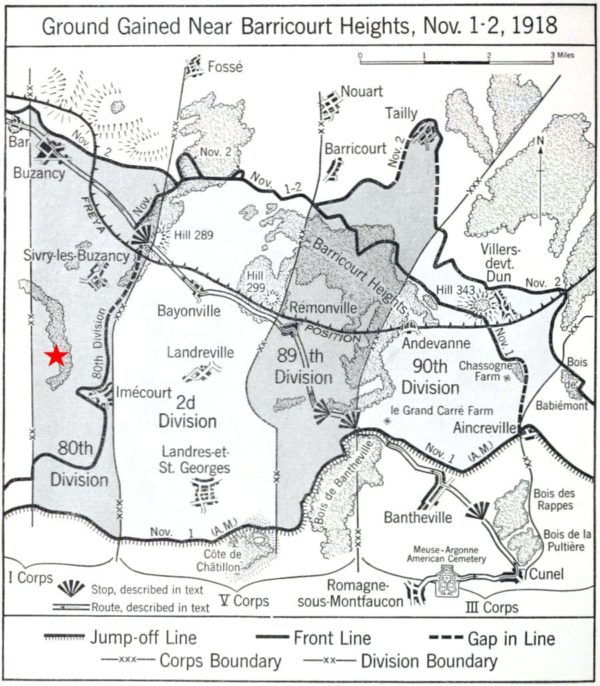

This map shows the weight and direction of principal attacks in November.33 A major attack was indeed made westward from Imécourt (south of Buzancy) by the 80th Division. It allowed the 77th and 78th Divisions to advance.

From all these accounts we learn Russell was very likely deployed the night of November 1st at Imécourt and defended the village from a German counter-attack. In the early morning hours of November 2nd, he took part in an active battle in the woods west of Imécourt and north of Alliepont. It was this battle that precipitated the German retreat that morning. He likely died before 4:00am during heavy fighting in the woods.

A map shows the front line the night of November 1 on the outskirts of Imécourt, where Russell was positioned.34 The woods through which he fought and died is indicated at left.

It is sad irony that Russell died then just as the battle culminated.

The Germans were in retreat. Their lines were broken, and the honor of having participated in the battle which compelled them to retreat along their whole front and which ended in complete disaster to them a few days later, was secure to the regiment forever. It had attacked at one of the important points on the front against some of the enemy’s best troops; had borne its burden of the day with heroic gallantry, and could thenceforth point with pardonable pride to its record in battle as the indisputable proof of what it could be depended upon to do.35

November 1st to November 11th: The 319th Infantry lost 60 killed, 31 died later of wounds, and 274 were wounded. Russell Stewart died quite literally during the final attack conducted by the 319th Infantry.

The regiment assembled northwest of Immecourt the evening of the 2nd, and marched through Sivry and Buzancy to Bar, the 3rd, where it camped in the open fields until the 5th. On the night of the 4th an enemy plane bombed the camp, wounding several men. On the 5th, the march was resumed; this time to the village of Sommauthe where the entire regiment billeted in houses very recently occupied by the enemy and still bearing the German signs. The first refugees were seen here, assembled in the village church where they were fed before being sent away in army trucks. And here, too, the last hostile fire [was] heard, a few long range shells breaking in the edge of the village. On the night of the 6th, the 1st Division relieved the 80th, and the march back from the line was begun the next morning.36

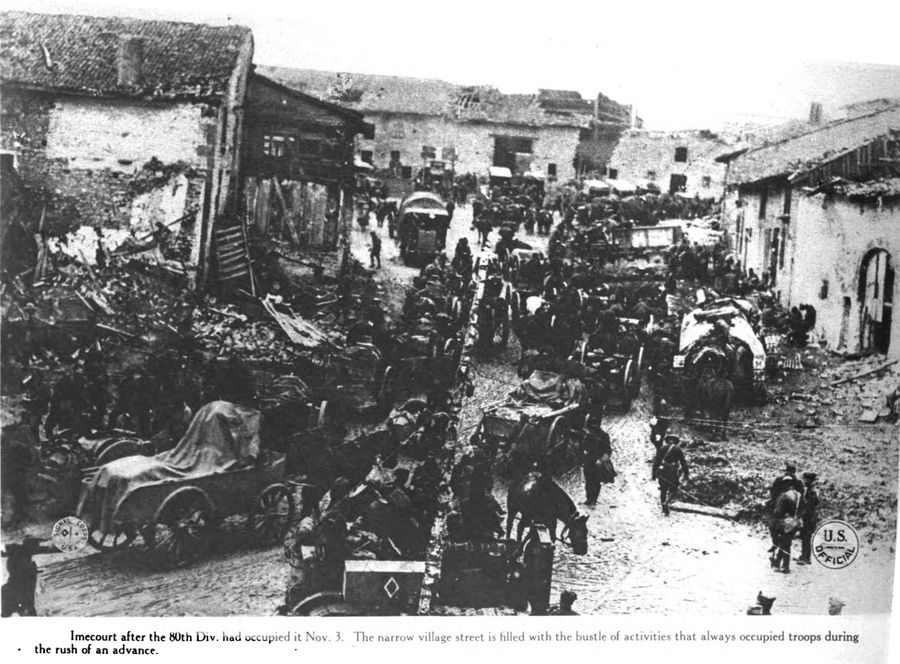

Shown here is the 80th Division rolling through Imécourt, the day after Russell died to liberate, then defend the village.37

Russell Stewart, having fought and suffered during the bloodiest days in the final weeks of the war died just as the Germans began their retreat in the third and final phase of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. This was the same day his regiment stopped fighting, four days before his division left the front, and nine days before the end of the war.

None of this was known to his mother and siblings back home. News of his death reached his mother’s eyes by telegram over a month later on December 5th. During that time the war had ended and everyone was celebrating. Christmas was approaching and his mother probably felt a sense of relief her son would soon be home. Instead there was only sadness and grief that Christmas.

Here is a photo of Russell’s grave in France probably taken shortly after the war and perhaps sent to the family.38 It wasn’t until the late 1920’s that today’s marble markers were installed.

News reached Indiana County, Pennsylvania, where Russell was born and raised.

Relatives in this county have been advised by the War Department of the death of Russell T. Stewart, who was killed in action in France, November 2. The deceased, who was aged 29 years, was born and reared in Buffington township and was a son of the late John G. Stewart, but for a number of years had resided at Turtle Creek. He is survived by his mother and three brothers and a sister residing at Turtle Creek. He was a nephew of Prof. J. T. Stewart, of town [Indiana, Pennsylvania]; William G. Stewart, of Dilltown, and C. C. Stewart, of Brushvalley.39

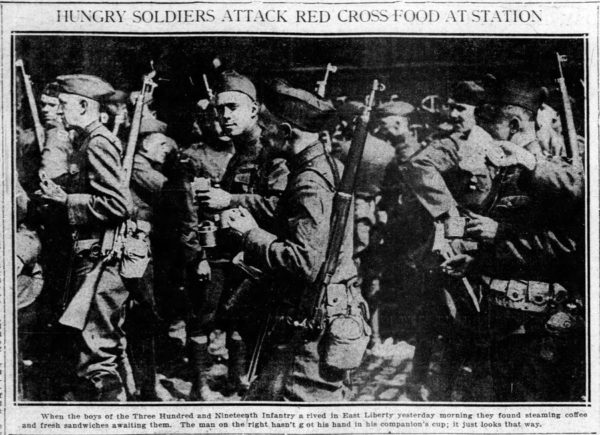

It wasn’t until June 1919, seven months after the armistice, the surviving men of the 319th Infantry finally came home.40 Russell Stewart stayed behind.

Only Moves Forward

During just two days of the battle, November 1st and 2nd, the 319th Infantry lost 55 men killed in action, while 29 men died later of wounds, and 255 were otherwise wounded. The 80th Division is the only American Division that took part in all three phases of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Russell also fought in all three phases. In total, the Division had 5,234 casualties between September 21st and November 11th.

It was during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive the 80th Infantry Division earned its motto: Only Moves Forward. I am proud to know that my granduncle Russell Stewart is one of the brave men who earned that motto.

Private First Class Russell T. Stewart is buried in the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial near Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, Lorraine, France.41 He is in plot C, row 25, grave 32, about 7 miles from where he died. There are 123 graves of the 319th Infantry here and 14,246 graves in total.42

The Regimental Commander wishes to commend, in the highest terms, the officers and enlisted men of the 319th Infantry for their gallant and efficient conduct in actions just closed. Your fighting ability and will to win have been proven of the highest order and fill a chapter in American history of which our Country will always be proud.

In this hour, our admiration and thanks go out to those who have so worthily and gallantly given their all to uphold the best traditions of the American Army and to insure the success of the great principle of humanity for which our Country is fighting.43

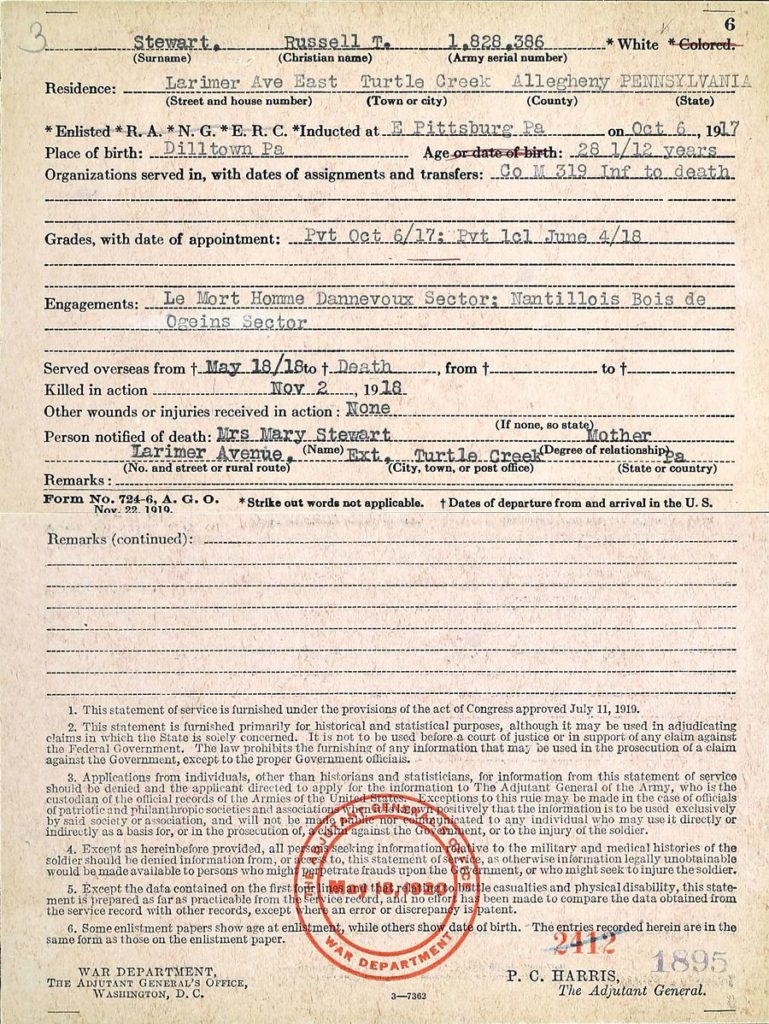

Additional Information

Russell’s service record provides more details.44 It indicates he served in Company M at the Le Mort Homme / Dannevoux Sector. Le Mort Homme is Dead Man’s Hill near Verdun, where the Meuse-Argonne Offensive began. Dannevoux is about 6 miles north of Le Mort Homme. He also served west of that sector, at the Nantillois / Bois de Ogons, or Ogons Woods, Sector.

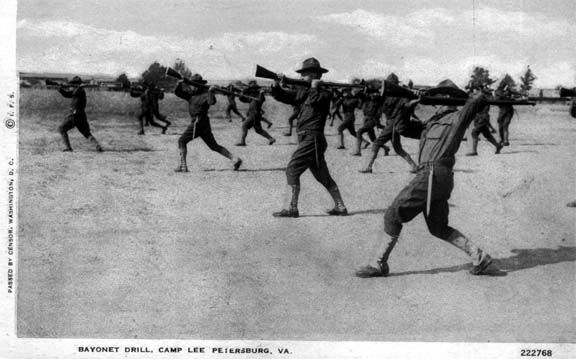

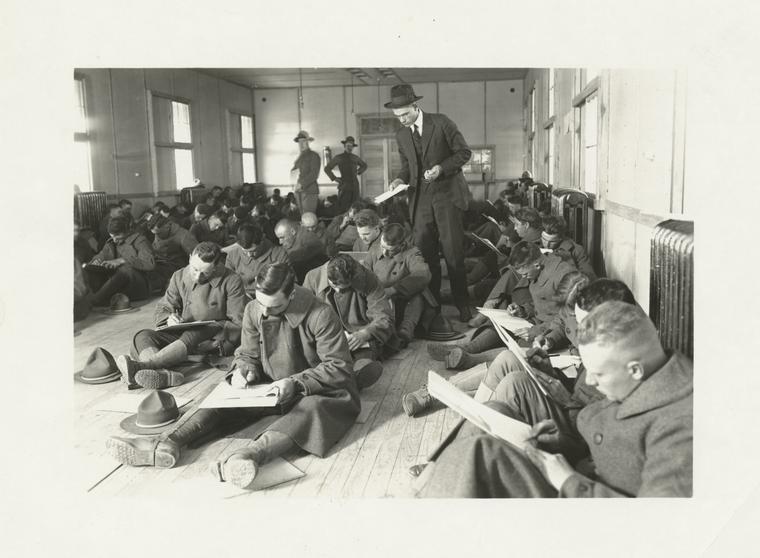

Several additional photographs from various sources provide glimpses of what Russell Stewart probably experienced.

Instructing the Latest Arrivals, Camp Lee, Petersburg, VA.45

Instructing the Latest Arrivals, Camp Lee, Petersburg, VA.45

Drilling in Front of the Barracks, Camp Lee, Petersburg, VA.46

Drilling in Front of the Barracks, Camp Lee, Petersburg, VA.46

Drilling at Camp Lee, Petersburg, VA.47

Drilling at Camp Lee, Petersburg, VA.47

Bayonet Drill, Camp Lee, Petersburg, VA.48

Bayonet Drill, Camp Lee, Petersburg, VA.48

Camp Lee, Va. Back from bayonet drill. Our boys in camp are becoming experts in the use of the bayonet under able Allied instructions.49

Camp Lee, Va. Back from bayonet drill. Our boys in camp are becoming experts in the use of the bayonet under able Allied instructions.49

Psychological test at Camp Lee, Va., November 1917.50

Psychological test at Camp Lee, Va., November 1917.50

Scene at Camp Lee, Va., clearing ground, December 1917.51

Scene at Camp Lee, Va., clearing ground, December 1917.51

A car load of hommes; Good-bye Calais; Calais 6-14-18; Spencer.52

A car load of hommes; Good-bye Calais; Calais 6-14-18; Spencer.52

Probably a view inside the French 40 and 8 rail cars used to transport troops from the port cities inland to the battle front. The cramped 40 hommes/8 chevaux rail cars could carry 40 men or 8 horses.

Montfaucon 9-28-18; Camouflaged guns in foreground.; Spencer – Altoona, Pa.53

Montfaucon 9-28-18; Camouflaged guns in foreground.; Spencer – Altoona, Pa.53

“Over the top”; St. Georges 11-1-18; Spencer – Altoona, Pa;

“Over the top”; St. Georges 11-1-18; Spencer – Altoona, Pa;

On their way to Immicourt having captured St. Georges about [?].54

Battleground – Immecourt 11-1-18.55

Battleground – Immecourt 11-1-18.55

Russell Stewart fought in this area on November 1, 1918 and perhaps witnessed this same view.

Company D, 319th Infantry.56

Company D, 319th Infantry.56

Company D is a sister to Russell’s Company M. This photograph illustrates the number of men in a company.

A shoulder patch, detail from a World War I tunic, depicting the 80th Infantry Division.57 Known as the Blue Ridge Division, it symbolizes the Blue Ridge mountains. Russell probably wore the same insignia.

- Robert M. Stewart, Stewarts 1776-1979 (N.p.: n.p., 8 July 1978), Appendix, Copy of Western Union telegram to Mary Stewart indicating Russell Stewart was killed in action 2 November.

- “United States Census, 1900,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-267-12861-87011-66?cc=1325221 : 5 August 2014), Pennsylvania > Allegheny > ED 535 Wilkins Township (excl. Wilkinsburg & E. Pittsburg Boroughs) > image 5 of 49; citing NARA microfilm publication T623 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

- West Virginia, Vital Research Records Project, FilmNumber 869969; Image 382, Stewart, Russell and Davis, Grace, 24 December 1909; Digital images, West Virginia Division of Culture and History, West Virginia Archives and History (http://www.wvculture.org/vrr/ : downloaded 29 May 2016); West Virginia State Archives and the Genealogical Society of Utah.

- “United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : Downloaded 29 May 2016), Russell Thomas Stewart, 1917-1918; citing , Allegheny County no 11, Pennsylvania, United States, NARA microfilm publication M1509 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,852,387.

- Jim Tipton, Find A Grave (http://www.findagrave.com/ : Downloaded 30 May 2016), PVT 1CL Russell T. Stewart, Memorial 55961495.

- Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 6 September 1917, Part of Immense Crowd which Bade Farewell to Draftees Yesterday; online archives (Newspapers.com : downloaded 25 June 2016).

- Dennis Stewart, MyHeritage.com, Robert M. Stewart Family (https://www.myheritage.com/site-148784861/robert-m-stewart-family : Downloaded 23 June 2016), Thomas Russell Stewart.

- Embarkation and Debarkation of the 80th Division, 1918-1919, “The Service Magazine,” Volume 8, Number 4, July 1927. 80th Division Veteran’s Association, (https://www.80thdivision.com/blueridge_wwi.html : viewed September 7, 2018), page 34.

- Maj. Charles Rossire, Jr., A Brief Diary of the 319th Infantry, “The Service Magazine,” Volume 4, Number 4, February-March 1923. 80th Division Veteran’s Association, (https://www.80thdivision.com/blueridge_wwi.html : viewed September 7, 2018), page 7.

- The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Men on a United States transport watching an encounter with a submarine.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1860 – 1920. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47db-1155-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

- American Battle Monuments Commission, American Armies and Battlefields in Europe: A History, Guide and Reference Book (US Government Printing Office, 1938), American Battle Monuments Commission, Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, Publications, (https://www.abmc.gov/cemeteries-memorials/europe/meuse-argonne-american-cemetery : downloaded September 7, 2018), page 170.

- American Battle Monuments Commission. 80th Division: Summary of the Operations in the World War. United States Government Printing Office, 1944, page 21.

- Josiah C. Peck, The 319th Infantry A.E.F. Paris: Clarke, 1919, page 25.

- Frederick Palmer, Our Greatest Battle (The Meuse-Argonne), New York, Dodd, Mead and Company, 1919, page 53.

- Charles Herr. Company F History, 319th Infantry: Pub. as a Matter of Record by the Officers and Men of the Company. Somerville, NJ: Unionist-Gazzette Association, 1920.

- Josiah C. Peck, The 319th Infantry A.E.F. Paris: Clarke, 1919, page 32.

- Josiah C. Peck, The 319th Infantry A.E.F. Paris: Clarke, 1919, page 32-33.

- Josiah C. Peck, The 319th Infantry A.E.F. Paris: Clarke, 1919, page 34.

- Ashby Williams, Experiences of the Great War (Roanoke, Virginia: The Stone Printing and Manufacturing Company, 1919), page 122.

- Ashby Williams, Experiences of the Great War (Roanoke, Virginia: The Stone Printing and Manufacturing Company, 1919), page 123-124.

- Ashby Williams, Experiences of the Great War (Roanoke, Virginia: The Stone Printing and Manufacturing Company, 1919), page 129.

- Frederick Palmer, Our Greatest Battle (The Meuse-Argonne), New York, Dodd, Mead and Company, 1919, page 275.

- Captain Arthur E. Hartzell, Meuse-Argonne Battle (Sept. 26 – Nov. 11, 1918), United States: Central Printing Plant, March 24, 1919, page 31.

- The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “From the edge of Bois de la Pultiere, looking S. by W. (205º azimuth) (mp. co-ord. 310.1-285.9 Dun-sur-Meuse) showing partly ruined town of Cunel, Meuse, taken by 80th Div. about Oct. 9, 1918, in Argonne-Meuse drive, Dec. 1918.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1860 – 1920. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-bda4-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

- American Battle Monuments Commission. 80th Division: Summary of the Operations in the World War. United States Government Printing Office, 1944, page 40-41.

- American Battle Monuments Commission. 80th Division: Summary of the Operations in the World War. United States Government Printing Office, 1944, page 44.

- American Battle Monuments Commission. 80th Division: Summary of the Operations in the World War. United States Government Printing Office, 1944, page 45.

- Josiah C. Peck, The 319th Infantry A.E.F. Paris: Clarke, 1919, page 37.

- Charles Herr. Company F History, 319th Infantry: Pub. as a Matter of Record by the Officers and Men of the Company. Somerville, NJ: Unionist-Gazzette Association, 1920, page 54.

- Jennings C. Wise, “General Brett and the Fighting ‘80th’,” How the Gallant Leader of the 319th and 320th Regiments of Infantry and 315th Machine Gun Battalion Played a Leading Role of the Bitterly Fought Battles of the World War, Facts Presented to Congressional Committee in Effort to Win Merited Rank for General Who Led Pittsburghers Through Decisive Phases of War, an article in “The Service Magazine,” Volume 3, Number 10, August 1922, pages 7-9, 31. 80th Division Veteran’s Association (https://www.80thdivision.com/blueridge_wwi.html : viewed September 6, 2018).

- “The Record of the ‘80th’,” a portion of General Order No. 19, Headquarters Eightieth Division, American Expeditionary Forces, France, 11 November, 1918, an article in “The Service Magazine,” Volume 3, Number 5, February 1922, page 13. 80th Division Veteran’s Association (https://www.80thdivision.com/blueridge_wwi.html : viewed September 6, 2018).

- Thomas W. Hooper, “The Truth of the Matter,” Being the Efforts of Those Who Were in a Position to Know the Exact Accurate Historical Facts Concerning the Movements of the Eightieth in the A. E. F., an article in “The Service Magazine,” Volume 2, Number 4, February 1921, pages 15, 26. 80th Division Veteran’s Association (https://www.80thdivision.com/blueridge_wwi.html : viewed September 6, 2018).

- American Battle Monuments Commission, American Armies and Battlefields in Europe: A History, Guide and Reference Book (US Government Printing Office, 1938), American Battle Monuments Commission, Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, Publications, (https://www.abmc.gov/cemeteries-memorials/europe/meuse-argonne-american-cemetery : downloaded September 7, 2018), page 186.

- American Battle Monuments Commission, American Armies and Battlefields in Europe: A History, Guide and Reference Book (US Government Printing Office, 1938), American Battle Monuments Commission, Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, Publications, (https://www.abmc.gov/cemeteries-memorials/europe/meuse-argonne-american-cemetery : downloaded September 7, 2018), page 276.

- Josiah C. Peck, The 319th Infantry A.E.F. Paris: Clarke, 1919, pages 37-38.

- Josiah C. Peck, The 319th Infantry A.E.F. Paris: Clarke, 1919, pages 38.

- William Emmet Moore and James Clayton Russell, U. S. Official Pictures of the World War, Showing America’s Participation, Washington, DC: Pictorial Bureau, 1920.

- Dennis Stewart, MyHeritage.com, Robert M. Stewart Family (https://www.myheritage.com/site-148784861/robert-m-stewart-family : Downloaded 23 June 2016), Thomas Russell Stewart.

- “Three More Boys Died for Country,” Article, The Indiana (Pennsylvania) Progress, 18 December 1918, Russell T. Stewart killed in action, Page 1; online archives (Newspapers.com : downloaded 19 June 2016).

- Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 10 Jun 1919, Hungry Soldiers Attack Red Cross Food at Station; online archives (Newspapers.com : downloaded 25 June 2016), page 10.

- Jim Tipton, Find A Grave (http://www.findagrave.com/ : Downloaded 30 May 2016), PVT 1CL Russell T. Stewart, Memorial 55961495.

- Graves Location of the 80th Division’s Dead, “The Service Magazine,” Volume 8, Number 4, July 1927. 80th Division Veteran’s Association, (https://www.80thdivision.com/blueridge_wwi.html : viewed September 7, 2018), page 25.

- Josiah C. Peck, The 319th Infantry A.E.F. Paris: Clarke, 1919, page 40, General Order Number 2 (PC), November 10, 1918, by Colonel James M. Love, Jr., commanding, 319th Infantry.

- “Pennsylvania, WWI Veterans Service and Compensation Files, 1917-1919, 1934-1948,” database online, Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015, Ancestry.com (http://ancestry.com: Downloaded 6 July 2016), Stewart, Russell T; citing World War I Veterans Service and Compensation File, 1934–1948. RG 19, Series 19.91. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg Pennsylvania.

- Opinicus Publishing Company (TheTroubleShooters.com : downloaded 28 Jun 2016), World War I, 80th “Blue Ridge” Infantry Division, Howard C. Spencer Scrapbook.

- Opinicus Publishing Company (TheTroubleShooters.com : downloaded 28 Jun 2016), World War I, 80th “Blue Ridge” Infantry Division, Howard C. Spencer Scrapbook.

- Opinicus Publishing Company (TheTroubleShooters.com : downloaded 28 Jun 2016), World War I, 80th “Blue Ridge” Infantry Division, Howard C. Spencer Scrapbook.

- Opinicus Publishing Company (TheTroubleShooters.com : downloaded 28 Jun 2016), World War I, 80th “Blue Ridge” Infantry Division, Howard C. Spencer Scrapbook.

- The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Camp Lee, Va. Back from bayonet drill. Our boys in camp are becoming experts in the use of the bayonet under able Allied instructions.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1860 – 1920. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-bdf2-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

- The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Pscycological [i.e. Psychological] test at Camp Lee, Va., 11-1917” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1860 – 1920. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-be92-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

- The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Scene at Camp Lee, Va., clearing ground, 12-1917” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1860 – 1920. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-bdf6-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

- Opinicus Publishing Company (TheTroubleShooters.com : downloaded 28 Jun 2016), World War I, 80th “Blue Ridge” Infantry Division, Howard C. Spencer Scrapbook.

- Opinicus Publishing Company (TheTroubleShooters.com : downloaded 28 Jun 2016), World War I, 80th “Blue Ridge” Infantry Division, Howard C. Spencer Scrapbook.

- Opinicus Publishing Company (TheTroubleShooters.com : downloaded 28 Jun 2016), World War I, 80th “Blue Ridge” Infantry Division, Howard C. Spencer Scrapbook.

- Opinicus Publishing Company (TheTroubleShooters.com : downloaded 28 Jun 2016), World War I, 80th “Blue Ridge” Infantry Division, Howard C. Spencer Scrapbook.

- Opinicus Publishing Company (TheTroubleShooters.com : downloaded 28 Jun 2016), World War I, Company D, 319th Regiment 80th Infantry Division-A.E.F. World War One, Earl Preston Gumbert family.

- The 80th Infantry Division (http://www.80thdivision.com/ : downloaded 4 Jul 2016), Photos, Dale R. Niesen Collection.

I edited my original post after I found more information. I conclude Russell was married to Grace Davis in 1909 and they had two children. I also discovered he was in Company M of the 319th Infantry Regiment. I added narrative about the locations of Company M during the battle, where known.

Loved your article! My granduncle, Robert Franklin Milby was in the 317th of the 80th Division. He also was killed on November 2, 1918. I am have trying to learn as much as I can about him.

UPDATE: More information about Russell Stewart has come to light as I continue my research. I edited this post to reflect those additions. Specifically, Russell sailed to France aboard the Zeelandia. I added a map showing the daunting system of German defensive trenches that Russell faced during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. I note Russell’s unit was held in reserve the first morning of the first phase of the offensive, but he did go “over the top” later in the morning.

I am now more confident in the exact location where Russell was killed in action. Amazingly, it is recorded in an article and in letters in The Service Magazine, a publication for veterans of the 80th Division published a few years after the war. They took issue with the divisional and regimental histories and wanted to set the record straight.

The original implication was that Russell was killed by shell fire while on a mission west of Imécourt to clear the woods, from which the enemy had already retreated. They supposedly encountered no resistance. Instead, he actively repulsed a German counter-attack at Imécourt the night of November 1, and took part in an offensive through those woods early in the morning, November 2. This was a decisive battle that caused the German retreat that morning, and allowed two other Divisions to advance.

Hello,

J’habitais à Imecourt quand j’étais jeune. J’y retourne régulièrement et je pense peut être savoir ou Russell a pu perdre la vie, enfin le bois ou ce serait arrivé

Je vais régulièrement à Romagne au cimetière, je saurai maintenant ou m’arrêter !

Cordialement

Francois Depaix

je vous laisse mon adresse mail [hidden]

Hi Francois,

Merci beaucoup. I hope to visit that area one day. Are there any memorials or plaques about the war in Imécourt?

Hi

Mon projet est de pouvoir écrire l’histoire de mon village. Nous sommes dans la période du centenaire et je concentre mes recherches sur cette période. Je souhaite lors de la cérémonie du 11 novembre expliquer comment le village a été libéré. Je cherche l’histoire de 3 personnes (allemande, française, américaine) pour illustrer ce moment.

J’ai donc trouvé votre histoire sur votre grand oncle. Est il possible de parler de lui, à partir de vos recherches, lors de cette journée ? et donc d’honorer sa mémoire pour notre petit village.

Il n’y a pas de mémorial ou plaque dans le village mais je souhaiterai que l’on puisse honorer la 80 e division et le 319 e d’infanterie.

Il y a sur you tube, si vous tapez 80 e division meuse argonne, un reportage d’époque, au tout début du film, sur le petit village d’imécourt.

Amicalement

François

Hi François,

Your project sounds great. It would be an honor if you included Russell Stewart. I am interested in reading about it from the other perspectives (French and German). I will contact you by e-mail to share more complete information. I saw that video a couple years ago, but I didn’t realize it was Imécourt at the time. Thanks for pointing that out.

Do you have a source for the photo of Company D of the 319th ? The website in the biblio is no longer working. My grandfather is in the back row of the photo and this is the only place I have found his company photo. Can you help? Thanks John

Sorry, that photo was the highest resolution I could find, and as you say, that site is no longer available. I recommend contacting Andy Adkins at http://80thdivision.com/Photos-AnthonyPanoramics/AnthonyPano_1.htm. Although he doesn’t seem to have Company D, he may still be able to help. He was very helpful in my case, in determining the photo of Company M was taken after the war, and thus did not show my granduncle.